by Christine Fortenberry and Grace Martell

Miss Gloria has worked at Louisiana State University for over twenty years. She is cherished by all, revered for her kindness, and she shows love to all who cross her path.

Miss Gloria has been a resident of East Baton Rouge Parish her entire life.Her parents raised her in a secure, albeit sheltered home; as she got older, she gradually realized that she was growing up in a place filled with hate. As a black creole teenager in 1960s Baton Rouge, she vividly recalls watching people being beaten for nothing more than advocating their rights. She could have been arrested for going on LSU’s campus past 6 pm, and even if she wanted to attend LSU she could not because it was an all-white campus. Even facing an environment steeped with prejudice, Miss Gloria maintained a spirit of kindness. “My daddy taught me that even when I wasn’t seen as a person, to see a person for what is in their heart.” Says Miss Gloria, “It’s not about the color of their skin but what’s in their heart.”

Tracing the Family

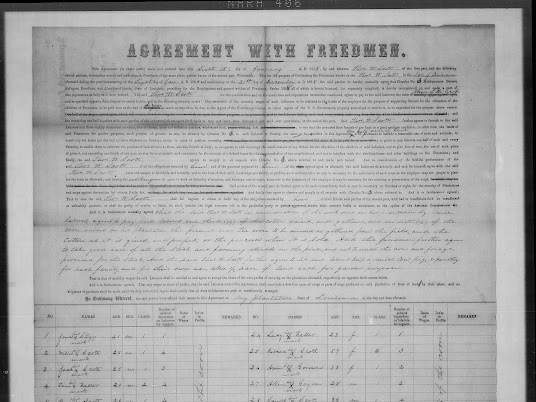

Miss Gloria’s family has lived in Baton Rouge for generations, and like many she aspires to trace her family lineage. The extensive research on a slave descendants’ family in East Baton Rouge Parish is a difficult task to undertake. It is not a straightforward Ancestry.com search. The aftermath of the Civil War and subsequent events led to the loss or destruction of many families’ lineage evidence and the destruction of records. In many cases, there were very few typical records in the first place. Slaves were not issued birth certificates or marriage licenses. They were not even allowed to get married, and “jumped the broom” instead. These married individuals had different last names, another obstacle in tracing.

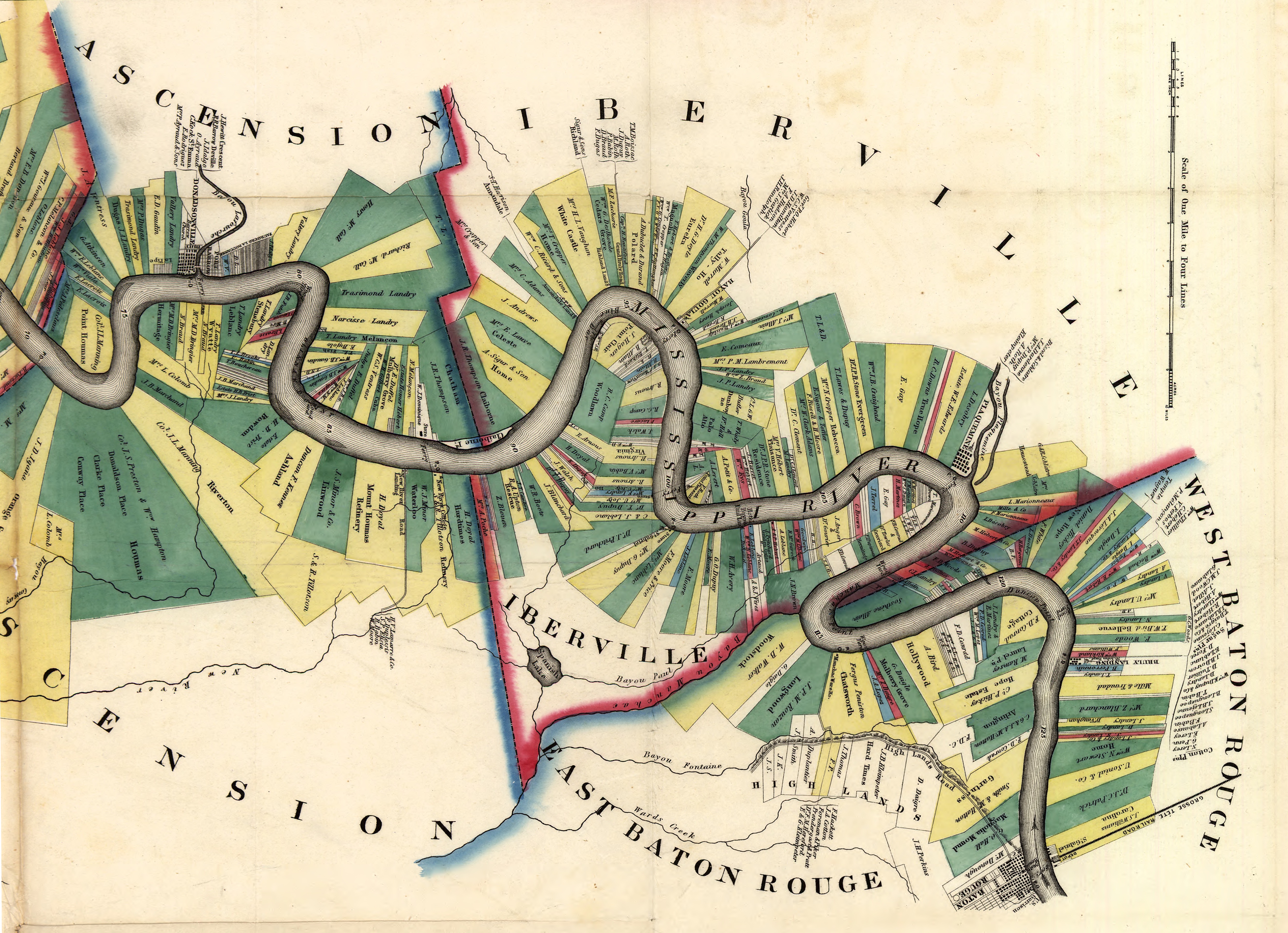

To trace further back than the late 1870s, connecting a descendant’s last name to the enslaver’s offers a lead to the plantation, opening avenues to explore further. To do so, usually the last name of the descendent is the same last name of the enslaver that will then lead to the plantation and hopefully further back as well. When Miss G was asked about names of members of her family to trace, she could only give her great-grandmother on her mother’s side and her grandparents on her fathers.

Findings

By using ancestry.com, draft registries, the national archives, familysearch.com, and local databases for each parish, Miss Gloria’s mother’s side of the family was traced all the way back to the 1870s. Her great-grandmother Emmaline Willis, born 1875, resided on Dedan Plantation, (no longer standing, in West- Feliciana Parish). She and her husband then had Stella Willis, who is Miss G’s grandmother. Stella then married Willie Lebray and lived in Baton Rouge. Further discoveries were Willie Lebray Jr.’s WWII draft registration.

Miss Gloria’s father, Matthew Williams (1920 – 1963), spoke French, but because of cultural stigma, her mother never allowed Miss G and her siblings to learn it. Her grandparents Viola Williams and Nee Nelson (1907 – 2000), along with her great-grandparents Amanda Nelson and Nee Scott (1873 – 1948), lived on Oakland Plantation after the Civil War. Her great-great grandparents Willis Scott (ca. 1840 – 1921) and Martha Torrance (ca. 1840) were enslaved on the plantation of Thomas W. Scott in East Feliciana Parish, known as Oakland Plantation.

Her great-great-great grandfather Mingo Scott (ca. 1824 – 1921) gained freedom, enlisted in the Union army in 1864, as a part of the first 2nd Regiment, United States Colored in the State of Louisiana posted originally in Vicksburg Mississippi and then moved into Louisiana. He was promoted to corporal in 1865. There is no documentation of a freedom contract for Mingo Scott; it is unknown whether he escaped bondage or was granted freedom by Thomas W. Scott.

Connecting the Dots

Families with rich histories pass down stories and legends to their descendants providing an understanding of the family’s identity. For descendants of slaves, oral histories are vital. Slaves were not allowed to learn how to read, let alone keep a personal account of their lives.

Miss Gloria’s family has a rich oral history of health remedies. Since slaves were denied medical care, these remedies were a necessity. Children did not wear shoes and would cut their feet on nails. They would take a white cloth and put kerosene on it and wrap their feet until the infection was drawn out. They would do the same with hog meat from hogs they hunted. They would salt it and put it on wounds until the infection was gone. If a baby was teething, they would take conqueror root, dry it out, and then sew it together to give to the baby to suck on. These stories provide for a deeper understanding of the struggles of the past. Miss Gloria’s grandmother used these remedies on her daughter and Miss Gloria and although Miss Gloria passed them on to her children, when asked if they used them, she said, “No, they go to the doctor,” with slight disdain in her voice.

Why it Matters

Miss Gloria’s desire to trace her family lineage is shared among many in Baton Rouge. For descendants of slaves, this quest may seem like an insurmountable task, but it can be done. Slavery is a recent memory. Miss Gloria’s stories provide an almost direct link to the voices of former slaves, often overlooked by conventional historical accounts. Passing down the stories of one’s family is important, and Miss Gloria had never sat down to write it all down or connect the missing pieces. Helping her trace and connect to her past gave her a piece of herself that she never had before. When shown the findings she said, “I can’t find the words to tell you what it means to me. I’m overwhelmed and happy. You brought me to tears.” Engaging in research not only honors the past but also empowers present-day individuals to reclaim their voices and heritage. Showing Miss G up until her great-great-great grandfather was a special moment as she reacted with pride and joy at the findings.

Sources:

Ancestory.com

“ESearch: Account Sign In.” eSearch | Account Sign In, cotthosting.com/laefelicianaexternal/User/Login.aspx?bSesExp=True. Accessed 6 Dec. 2023.

“Louisiana. Census 1830.” FamilySearch.Org, http://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9YYN-3SHZ?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AXHPF-DSS&action=view. Accessed 6 Dec. 2023.

“Military Service Records.” FamilySearch.Org, http://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L98J-9LBB?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3ACYTH-4GW2&action=view. Accessed 6 Dec. 2023.

National Archives. World War II. Willis Scott. Order Number 12297.

U.S. Department of the Interior. (n.d.-a). Battle unit details. National Parks Service. https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-battle-units-detail.htm?battleUnitCode=UUS0002RAL0C

U.S. Department of the Interior. (n.d.). NPGallery asset detail. National Parks Service. https://npgallery.nps.gov/AssetDetail/NRIS/80001720