by Emma Booker and Sydney-Blair Pickle

During the Antebellum Era in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Dick Glover’s life emerged as a powerful symbol of the enduring struggle for freedom and human dignity that enslaved people experienced. His remarkable journey began with his unjust imprisonment in 1844 and unfolded through his multiple acts of defiance against a system that sought to dehumanize him. In essence, Dick Glover’s life epitomizes black resistance.

Although his story is profoundly unique and personal, his relentless pursuit of freedom not only highlights his own resilience but also the collective resilience shared by countless enslaved people. In a society that sought to exploit and profit from the lives of enslaved people, Dick Glover’s courage and defiance stood as a beacon of hope and resistance. Dick Glover’s narrative effectively offers a compelling lens through which to understand the complexities of the Antebellum South and the unbreakable dedication of those who fought to resist the oppressive bonds of slavery.

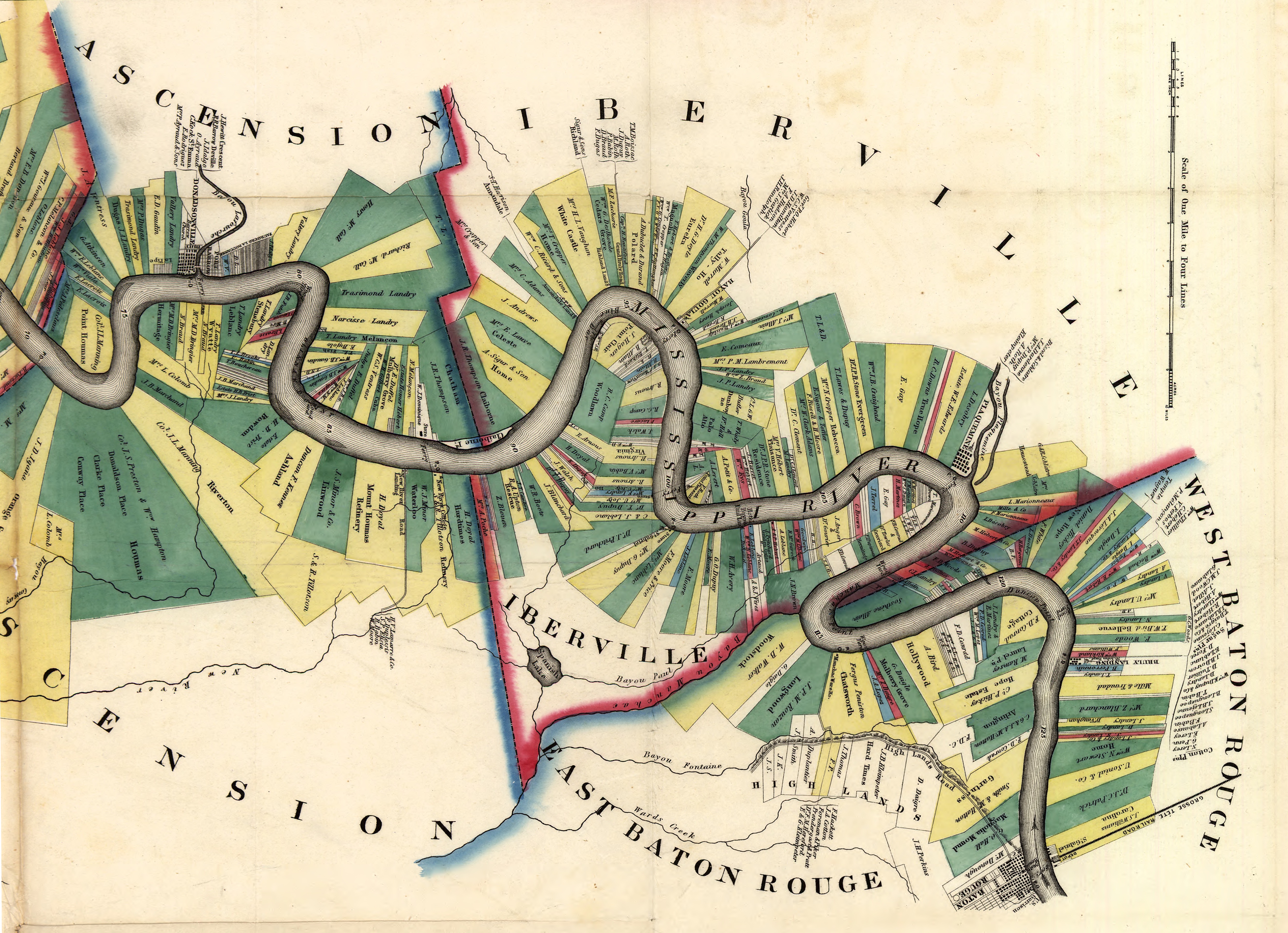

Dick’s tumultuous journey commenced when he was committed to the Louisiana Penitentiary on February 18, 1844. His fate was unfortunately sealed based on suspicions that he was a runaway slave. This unfortunate beginning laid the foundation for a series of challenges that would ultimately shape his unwavering pursuit of freedom. In 1846, a newspaper article shed light on Dick’s situation.The state of Louisiana planned to sell him at auction because his enslaver had not claimed him in the two years that he had spent in the state penitentiary. The decision to sell Dick underscores the dehumanizing nature of a system aiming to capitalize and benefit from the lives of those caught within it. Even before his imprisonment, Dick’s act of running away exemplified black resistance against the repressive institution of slavery. The theme of is defiance remained as he continued to challenge the very core of the inhumane system that sought to confine him.

During the 1850s, the Louisiana Legislature decided to revive the grim practice of state-owned slavery. State-owned slavery involved using enslaved prisoners as laborers on public infrastructure projects. Dick became apart of this system when he was transferred from the state penitentiary to the Board of Public Works in 1857. The Board of Public Works, a government agency responsible for overseeing public works projects, presented new obstacles that challenged Dick’s strength and determination.

From April 1, 1858, until July 15, 1858, Dick “labored faithfully” under the coercion of the Board of Public Works as he worked on the construction and maintenance of various public infrastructure initiatives. However, he eventually reached a point where passive compliance no longer sufficed within this unbearable system. Seizing an unexpected opportunity one day, Dick took matters into his own hands with an act of resistance aimed at liberating himself from state-sanction slavery. His bold escape served as a potent reminder that deep-rooted defiance persisted in the face of institutionalized oppression. Dick’s persistent dedication to freedom provided undeniable evidence that even in the most dire situations, his indomitable spirit could not be completely subdued.

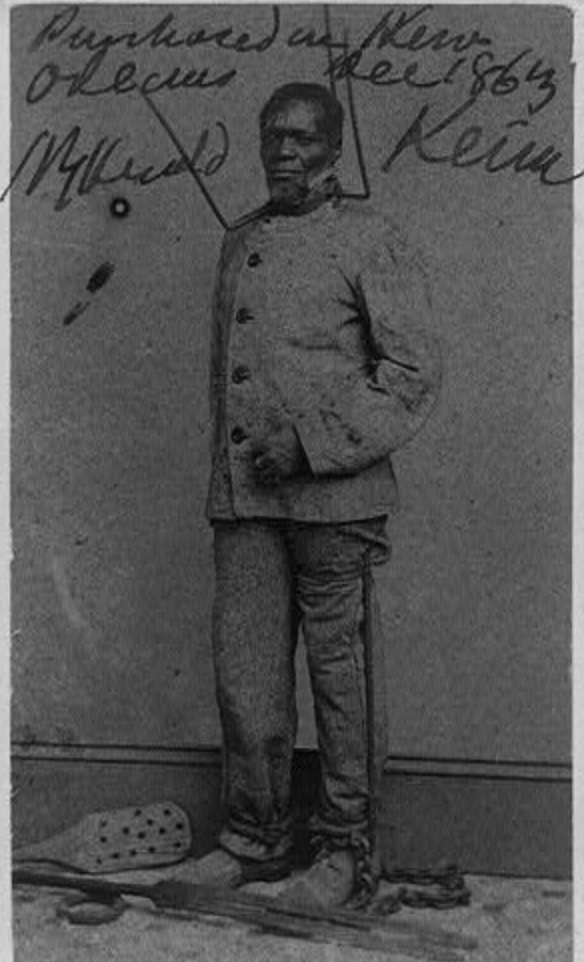

Despite his escape, Dick’s freedom was short-lived. He was recaptured and thrust back into the custody of the state of Louisiana. Due to his rebellious nature, the state branded Dick as “incorrigible,” a stigmatizing label that led to the state’s decision to put him up for sale on the New Orleans auction block. Newspaper articles chronicled this lengthy, harrowing ordeal while Dick was for sale in New Orleans from April 25, 1860, to June 9, 1860.

Such deplorable practices stripped enslaved individuals like Dick of their fundamental dignity while reducing them to mere commodities devoid of basic human worth. The very act of staging these auctions effectively transformed enslaved people into objects for trade and ownership. This haunting symbol showcased the objectification enslaved people endured at the hands of Southern society during the Antebellum Period.

The fate of Dick following the 1860 slave auctions in New Orleans is shrouded in mystery, as there are no available records that disclose who purchased him. However, a few individuals bearing his name and matching age appear in several historical documents that originated in the period after the Civil War. These references can be found in sources like the Freedmen’s Bureau Field Office Records and the United States City and Business Directories. While it is tempting to speculate that these mentions refer to the Dick discussed in this article, establishing a definitive connection proves to be exceedingly difficult. The ambiguity of these records leaves a gap in the narrative, offering only glimpses into what might have been his life after emancipation.

Since his story is deeply embedded in the history of Antebellum Baton Rouge, the life of Dick Glover exemplifies the unyielding spirit of resistance that defined an era of African American struggle. His journey, characterized by imprisonment, escape, and dehumanizing auctions, serves as a somber reminder of the profound injustices endured by enslaved individuals and their unrelenting quest for freedom and dignity. Dick Glover was not simply an enslaved person who was constantly attempting to escape; instead, he embodied a symbol of black resistance as he proved to be an extremely disruptive force to all of his enslavers. While the details of his life after emancipation remain elusive, Dick’s narrative encapsulates the shared hardships experienced by countless other enslaved people who dared to challenge the inhumane system of slavery. Dick Glover’s story resonates as a timeless testament to the enduring resilience and resistance of the numerous enslaved individuals who courageously defied the oppressive bonds of slavery in aAntebellum Baton Rouge, ensuring that his legacy would serve as a source of inspiration and education for generations to come.

Sources

Board of Directors of the Louisiana State Penitentiary, Annual Report, 1856, Louisiana State Penitentiary.

Board of Directors of the Louisiana State Penitentiary, Biennial Report, 1854, Louisiana State Penitentiary.

“Louisiana Freedmen’s Bureau Field Office Records, 1865-1872,” images, FamilySearch.

Louisiana State Engineer, Annual Report of the State Engineer, 1858, Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections, Louisiana State University Special Collections.

“United States City and Business Directories, ca. 1749 – ca. 1990”, database, FamilySearch.

Weekly Advocate, 15 Apr. 1860, p. 6.

Weekly Advocate, 3 June 1860, p. 6.

Weekly Advocate, Morning ed., 25 Mar. 1846, p. 3.