by Jacob Voisin

The use of enslaved people’s labor and the existence of slavery in Louisiana prior to the civil war was deeply entrenched in the economic, social, and cultural fabric of the region. However, virtually nothing is attributed to the existence of enslaved men owned by the state and headquartered out of Baton Rouge, who sacrificed themselves to keep this state metaphorically and literally afloat. This article will analyze the very existence of these historical ghosts, exploring just how deep the reach of slavery was in reality.

The name designated to the men who were owned by the state of Louisiana was the State Force. The State Force of Louisiana was headquartered in Baton Rouge, on state capitol grounds. The apartments now, in which many of our state politicians reside while staying at the state capitol, were once the barracks and command posts of which the orders to disperse and consolidate the State Force were given. At the height of the State Force’s existence, as many as 135 enslaved men (formally “Hands”) were put to work across the state of Louisiana, toiling under the control of the State Engineer.

A Life of Danger

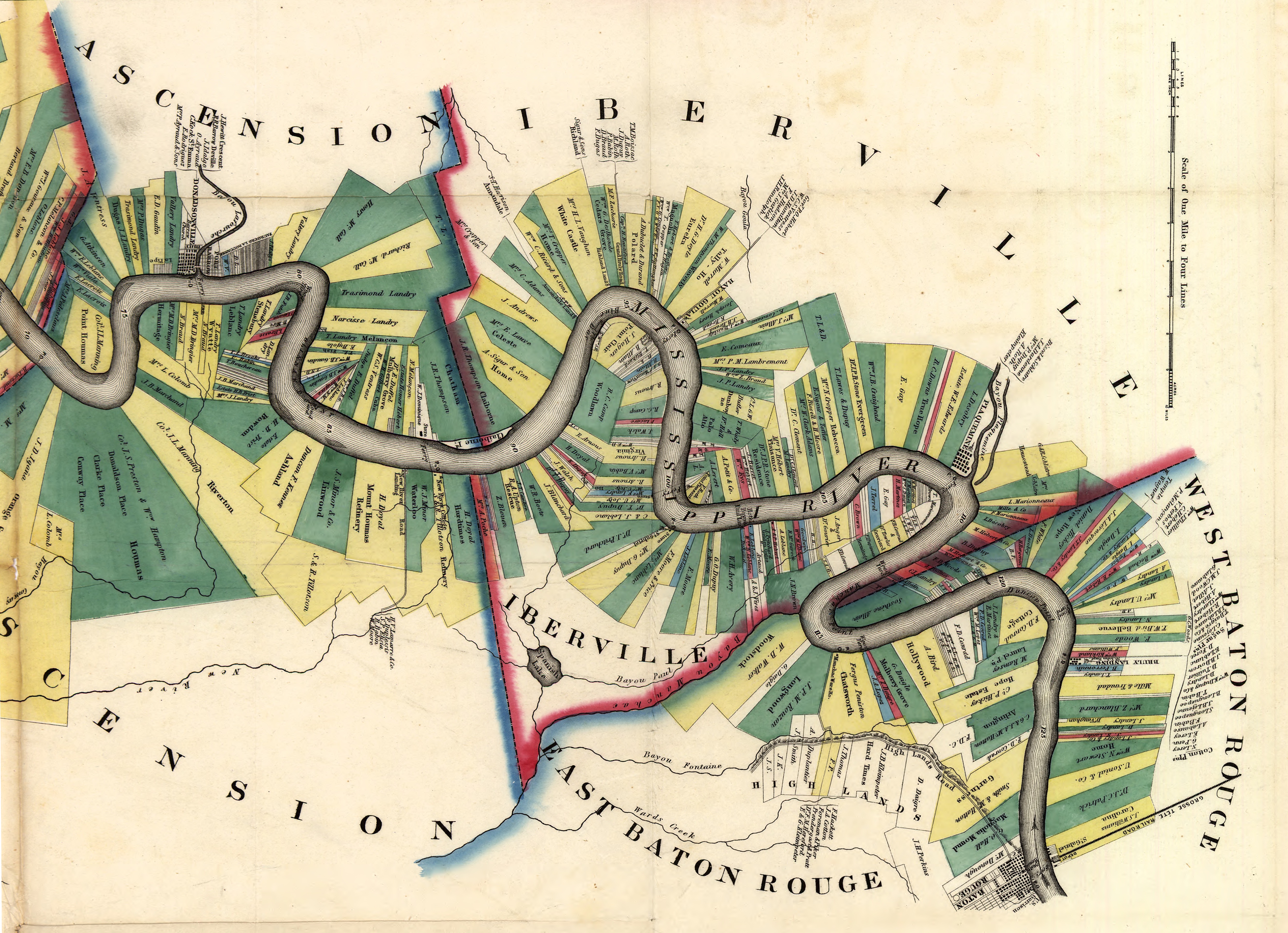

These enslaved men were expected to create, repair, and innovate upon state infrastructure projects, prior to the dissolution of the State Engineer’s office in 1860. With special reference to the State Engineer annual report, individuals achieve an understanding of the work these men were subject to “Capt. White, with twenty hands, arrived here on the 10th of January, after doing all the work in Bayou Cornie…and was immediately sent with thirty hands to Bayou Sorrel to cut all the leaning trees upon the banks of that bayou, which heavily obstructed navigation.” This type of work was extremely difficult and dangerous, oftentimes resulting in death or injury of the enslaved individual. In 1854, the State Force lost 10 men to drowning in a seven month period, as well as six more to water-borne disease, the price of which is sadistically calculated through a cost-analysis carried out by state engineer Louis Hebert in 1855 totalling a single slave to be worth $16 of state funds.

Despite the selfless contributions by the enslaved members of the State Force, many in power in Baton Rouge felt that the use of the State Force was worthless for these infrastructure projects. In fact, many believed that the use of white laborers was not only better, but the quality and amount of work would surpass that of the “state hand”. This argument stemmed from the racist belief that blacks were mentally and physically inferior to their white masters. However, using the state’s cost analysis of 1855, the cost of utilizing slaves in comparison to paying for white labor found that, on an annual basis, providing state slaves with provisions compared to white laborers found a difference of $23,000 per year or $852,000 per year in today’s money, implying that state slaves were vastly cheaper to the white alternative. In a deeply racist quote, the state engineer of 1857 explains his defense of the use of state slaves “…they forget that one state slave is not worth fifty of their own slaves.” As well as this, the state engineer believed that State slaves could work in far less suitable climates as well as during the sick season yielding higher results than hired white labor.

The Possibility of Insurrection

In 1860 following years of internal turmoil stemming from the Campté situation, the office of state engineer was dissolved and State Force slaves were sold off to various plantations in the surrounding regions of Baton Rouge. In the final state engineer annual report of 1860, the state engineer cites the state government’s inability to see the use of these slaves as necessary, and the growing danger of possible insurrections was too dangerous to continue utilizing these individuals. In a final act, the state engineer of 1860 implemented a plan to keep invalid slaves, or slaves not capable of hard work, on state capitol grounds with the task to upkeep the surrounding area . This system is still in place today at the state capitol in Baton Rouge using inmates.

In the most famous account on the existence of the State Force, word of a “servile” slave insurrection is mentioned on July 4th 1854, supposedly perpetrated by State Force hands. This account is traced to the Campté settlement, which was some miles north of Lafayette. Those fearing an insurrection believed State Hands conspired with white boat captains in an attempt to free themselves from state enslavement. Paranoid townsfolk descended upon the state force’s camp where anywhere from 16-35 men were arrested and held in Natchitoches. Evidence of this can be found in the Daily Gazette and Comet newspaper on July 4th, 1854 “White men are implicated as the leaders of the blacks, but, so far, no overt act committed by them has been discovered. Yesterday a large party of civilians descended to the bank of the river, where the state hands were at work and arrested some 16 or more of them.” The slaves were freed following the state engineer threatening legal action against all involved for the “improper seizing of state assets” and no case was ever brought against the state hands. This instance eventually led to the nail in the coffin when it came to the office of the state engineer and its presiding over the State Force.

In 1860 following years of internal turmoil stemming from the Campté situation, the office of state engineer was dissolved and State Force slaves were sold off to various plantations in the surrounding regions of Baton Rouge. In the final state engineer annual report of 1860, the state engineer cites the state government’s inability to see the use of these slaves as necessary, and the growing danger of possible insurrections was too dangerous to continue utilizing these individuals. In a final act, the state engineer of 1860 implemented a plan to keep invalid slaves, or slaves not capable of hard work, on state capitol grounds with the task to upkeep the surrounding area . This system is still in place today at the state capitol in Baton Rouge using inmates.

Their Legacy in Louisiana

The echoes of these men and their work can be seen still today along the banks of Lockport, Alexandria, Shreveport, and all the way to the spillways and bayous that inhabit Baton Rouge and the towns surrounding it. The State Force of Louisiana kept the state above water for decades for individuals who only wished to drown the existence of these men.

Sources:

Annual Report of the State Engineer: To the Legislature of the State of Louisiana. 1853.

Annual Report of the State Engineer: To the Legislature of the State of Louisiana. 1855.

Annual Report of the State Engineer: To the Legislature of the State of Louisiana. 1857

Annual Report of the State Engineer: To the Legislature of the State of Louisiana. 1860

Antebellum Louisiana: Agrarian Life, http://www.crt.state.la.us/louisiana-state-museum/online-exhibits/the-cabildo/antebellum-louisiana-agrarian-life/. Accessed 15 Nov. 2023.

Baton Rouge Daily Gazette and Comet. 1854.

“History of Slavery in Louisiana.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 1 Oct. 2023, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_slavery_in_Louisiana.