by Elisabeth Paternostro

Introduction

In May of 1844, the local newspaper, Baton Rouge Gazette, printed a notice for a runaway slave:

“TEN DOLLARS REWARD – Will be given for taking up and putting in Jail the negro woman name Jane aged about 34 years. She is well known in this town, and is believed to be harboured by some person here or in the neighborhood. She is stout built, of comely appearance, has regular features, is much given to talking, and very much addicted to lying. An additional reward will be given for information that will lead to the conviction of any person harbouring said slave.”

While the advertisement speaks little of the enslaved women herself, just simply her name, age, and “comely appearance,” between the lines portrays the intelligence and skills possessed to hide in plain sight. The brief notice gives insight into a long story of an enslaved woman named Jane who, by acting in defiance of the oppressive system she was likely born into, risked everything for a chance at freedom.

However, her act of defiance was perverted as a criminal act against her enslaver, and the very institution they wished to uphold. Men were paid to track her down, and the Baton Rouge patrol was likely deployed. Her “regular features,” something meant to disguise her, were likely used to identify her amongst the residences of the town.

Perhaps she knew the people of the town very well, and perhaps they enjoyed her company as she received help. While we do not know her full story, we know of the ordinances insisting on her, among many others’, capture and the intensifying rhetoric around the incarceration of enslaved people.

This blogpost will explore how people like Jane were policed in Baton Rouge and its surrounding parishes. Additionally, it will explore how these policing efforts evolved while the underlying motivations were perpetual.

Emergence of Policing

Following the Louisiana Purchase, rudimentary ordinances were enacted to establish public order in the New Orleans territory. As early as 1806, Louisiana legislature began to regulate the whereabouts, proceedings, and possessions of enslaved people. These statutes, referred to as the “Black Code,” laid the foundation for controlling enslaved people and included provisions directly related to patrols and policing, especially regarding runaway slaves:

Sec. 19. “And be it further enact, That no slave shall by day or by night carry any visible or hidden arms, not even with a permission for so doing, and in case any person or persons shall find any slave or slaves, using or carrying such fire arms, or an offensive weapons of any other kind, contrary to the true meaning of this act, he, she or they lawfully may seize and carry away such fire arms, or other offensive weapons.”

Sec. 20. “And be it further enacted, That the inhabitants who keep slaves for the purpose of hunting, shall never deliver to the said slaves any free arms for the purpose of hunting, without a permission by writing, which that not serve beyond the units of the plantation.”

Sec. 34. “And be it further enacted, That every justice of the peace is authorized in his district upon information or evidence received under oath, to go personally, or to send an order to any constable, or any other person, requesting him to order the attendance of such a number of person, as he may think proper to disperse any number of runaway slaves, or others who may against the public peace, and also to search all such places where arms, ammunition or stolen goods may be supposed to be concealed, and to apprehend all slaves who may be suspected of having committed crimes, of any nature whatsoever, and to prosecute them pursuant to this act.”

Although there are a plethora of sections listed beneath the Black Code, the aforementioned statutes work to reinforce control over the autonomy and possession of enslaved peoples, subjugating them to penal persecutions and potential encounters with the burgeoning police department. While these laws attempt to ensure “public order,” they arbitrarily subject colored people, both enslaved and emancipated, to stringent provisions all in an attempt to further control the African population within Louisiana.

Eventual revisions and additions of the statutes previously constituted in the 1806 “Black Code” were purported to be ad-hoc laws. However, subsequent ordinances were designed primarily to maintain the institution of slavery and ensure the patrolled order of the enslaved population to suppress any form of resistance. To further establish these suppressive laws policing slaves, Baton Rouge, as well as other parishes within Louisiana, adopted organized slave patrols.

Structure of Slave Patrols

Contrary to popularly held conceptions, enslaved people were not solely supervised by overseers and drivers on plantations. While overseers played a role in the subordinating slaves to racially driven patrols, these patrols were often organized by the State, local parishes, and even the town. For example, in 1822, a new ordinance relative to patrols passed, establishing an organized and endorsed police force. The ordinance states:

“Be it ordained… it shall be the duty of every free white male inhabitant of the town of Baton-Rouge, of the age of sixteen years of age and upwards, to patrol the streets, within the limits of the town of Baton-Rouge, when notified to do so by the Town Officer.”

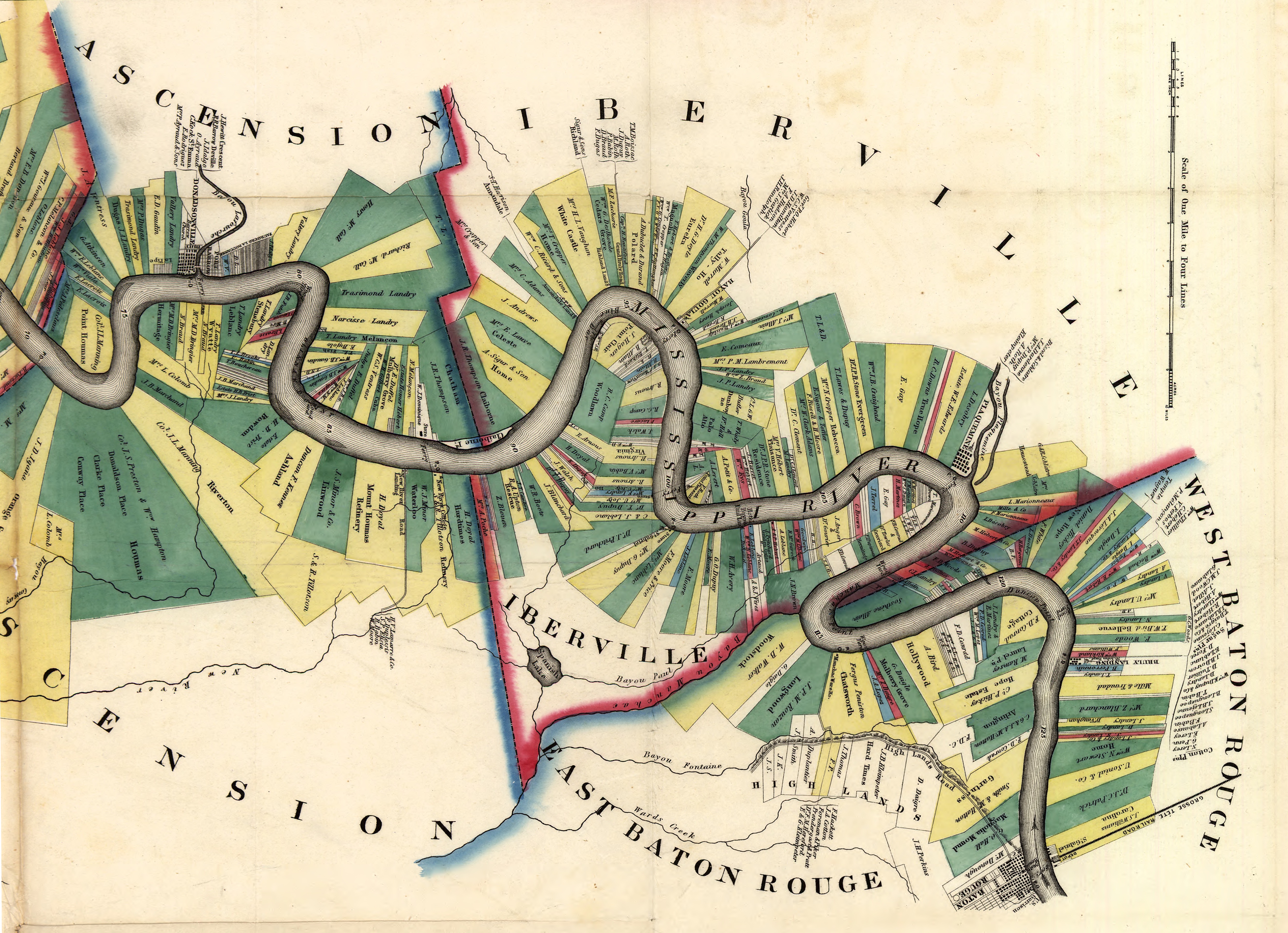

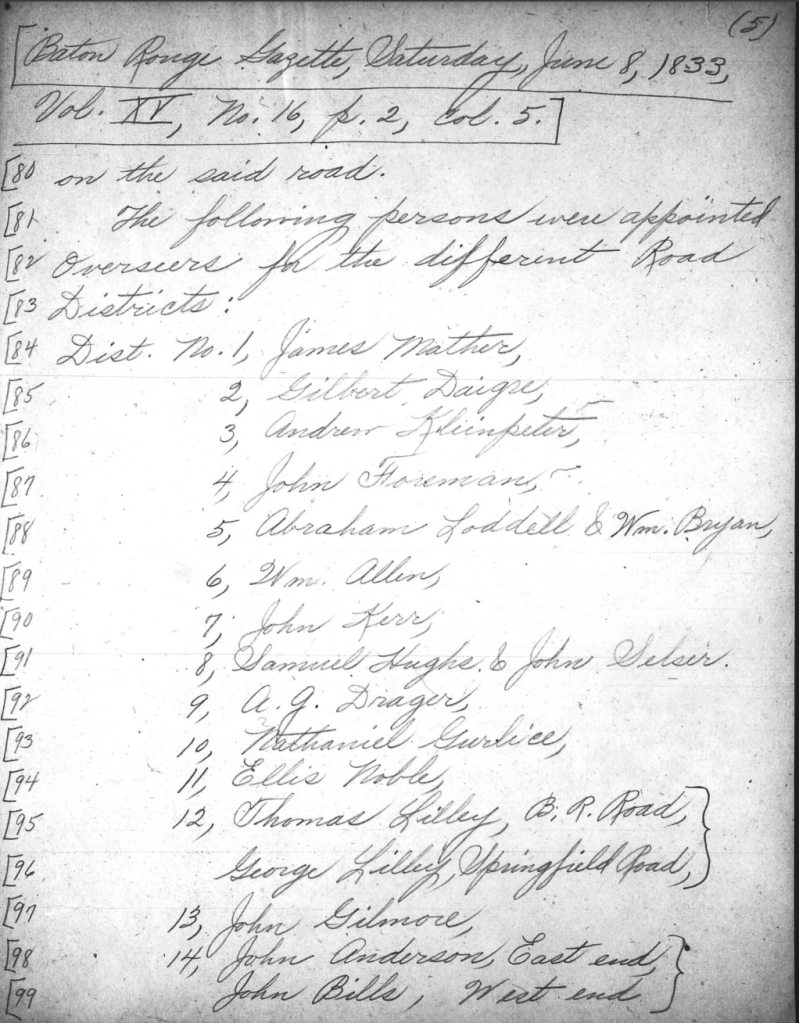

As patrols became an established system of “law and order,” the structure of patrols became codified into law. Ordinarily, patrols were authorized no less than once and nor more than twice per week in each patrol district. Patrol districts were determined similarly to police jury districts where directors of patrols were announced. All directors and captains of patrols were required to be slaveholders or sons of slaveholders. Additionally, all other white men between the ages of 16 to 50, within their respective area, were expected to adhere to their patrol duty if called upon. The division of police districts was entirely up to the director’s discretion. Each patrol consisted of approximately five people, all listed out during that month’s jury duty, and were made out on either foot or horseback according to the captain’s orders.

The patrolling officers were additionally endorsed for their duty, each man receiving 50 cents per round of patrolling while the captain received 75 cents. The director received an upwards of $50 per year for his duties. Penalties were also inflicted upon acts of insubordination, equating to $3 for any person subject to patrol refusing the orders of the captain and $5 for the captain refusing to file a report to the director. These wages and fines were incentives toward the white male population to adhere to orders and conform to organized subjugation.

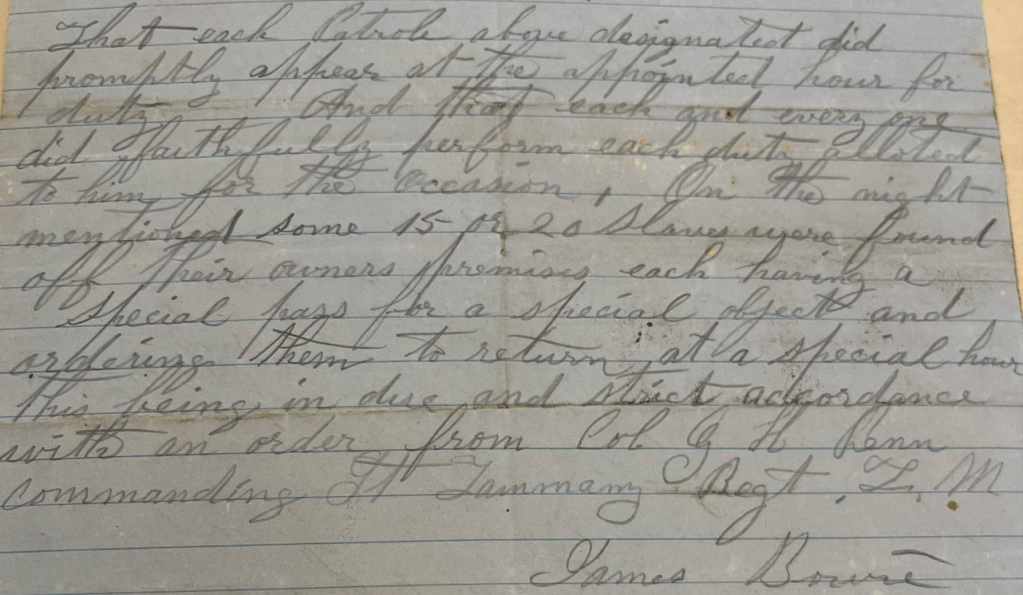

Reports were protocol, concluding every patrol. Captains were expected to document the events which occurred even if nothing paramount did occur. Refusal to do so would result in a fine, as previously stated. Ordinary reports detailed who, if anyone, did not obey orders and if they encountered any enslaved people.

For example, Captain James Bowie details his night patrol in Covington, LA, in 1862. He begins by stating that “each patrol… did promptly at the appointed hour for duty.” He then goes on to detail his encounter with “some 15 or 20 slaves… found off their owners’ premises.” Issued reports were standard for patrol captains from the development of the slave patrols until the eventual dissolution following the Civil War.

These reports not only contained information regarding the patrol, but also acted as a blueprint to refine and revise positions of public order and slavery. These reports were used in both police juries and city councils to establish new police codes and conduct. These newly adopted codes would allow for more stringent control over the enslaved population of Louisiana, rebuking routes for fugitive slaves and preempting any type of slave rebellion and resistance. As a result of, laws regarding the conduct of patrols grew more arbitrary and rigorous as the institution of slavery became more contested, heavily hindering enslaved peoples’ chances of successfully escaping bondage.

Fear and Escalation: Policing in Times of Panic

Rudimentary slave patrols were initially developed to ensure “public order” within the new United States territory of Orleans. However, policing of enslaved individuals gradually became more stringent as tensions regarding slavery became heightened, uprisings were attempted or successful, and the state interest in upholding the institution of slavery grew stronger.

The Black Code established in 1806 through the first session of the first legislature of the Territory of Orleans enacted the first set of laws governing the enslaved population of Louisiana. These codes were directly reflective of the legislative concerns at the time who sought to not only deter illicit affairs from white and black felons. Legislators soon proposed municipal institutions would benefit the Territory of Orleans and improve the conditions and public order of the newly adopted state. However, another motivation toward the establishment of patrols was to further subjugate enslave people as the institution of slavery were an essential part of the economic growth of the south.

Furthermore, as the enslaved population grew throughout the 19th century, the amount of runaways coincided. Fugitive slaves posed a threat to the institution of slavery as their self-imposed manumission alluded to possible retaliation in the eyes of white southerners. Any real news of enslaved people wreaking havoc added to these anxieties and lead to subsequent slave patrol laws. For example, the German Coast Uprising of 1811 consisted of an expanding hoard of slaves fighting with whatever weapons or arms they could acquire, setting plantations on fire, and concomitantly combating the local militia. Coincidently, ordinances were passed following the slave insurrection. By 1814, Louisiana Legislators had enacted laws requiring “every person being the proprietor of a plantation… shall be bound to have permanently… a white person for every thirty slaves working… to oversee the said slaves and maintain a good police among them.” These laws not only ensured cohesiveness amongst plantations, but were also a possible consequence of the German Coast Uprising as it was thought that securing order on plantations would deter enslaved people from insurrection and escape.

Nonetheless, marooned slaves within the swamps purportedly wrecked havoc around 1820s. According to the Louisiana State Gazette, “a large body of militia of Norfolk county are ordered on a tour to patrol the forests and swamps… and thus relieve the neighboring inhabitants from a state of perpetual anxiety.” As reported, a band of runaway slaves retreated into the swamps “in which most of them have been all their lives… [and] which they are perfectly familiar.” The article goes on to speculate their goals, insisting their “first object is to obtain a gun” to eventually “accomplish objects of vengeance.”

“No individual after this can consider his life safe from the murdering aim of these monsters in human shape” – Louisiana State Gazette, 1823

While there is no evidence to suggest the exact motivations of these fugitive slaves, the article successfully convinced the white residences of the surrounding area of an insidious presence of slaves marooning within the swamps. “The topography of this section of the country being calculate to favor their murderous purposes and to shield them from discovery, detection in the execution of their horrid purposes is almost impossible without an accident.” To ensure peace and order within the Baton Rouge Parish and its surrounding areas, ordinances regarding policing of enslaved individuals were revised, and additional precautions were taken. The aforementioned ordinance permitting the patrol of streets and surrounding areas of the town was enacted in 1822.

Rudimentary patrols were established, marking the point at which an enslaved person’s escape from their enslaver was remarkably more difficult. As the institution of slavery became more paramount to the economy of the south, laws restricting movement of slaves and permitting patrols’ prohibitory actions became more stringent and constrained. For example, the cotton revolution of the 1830s marked a point in which southern planters became essential to the South’s overall GDP. Enslaved people became an essential part to the commonwealth of the South, and to their planter’s overall wealth. Additionally, speak of Nat Turner’s Revolt in 1831 as well as an ongoing slave rebellion in Cuba, as documented in the Baton Rouge Gazette, hastened apprehension to the idea of overt and convert resistance. By the 1840s, harsh penal laws were implemented to ensure a decline in overt and convert resistance and keep the institution of slavery afloat.

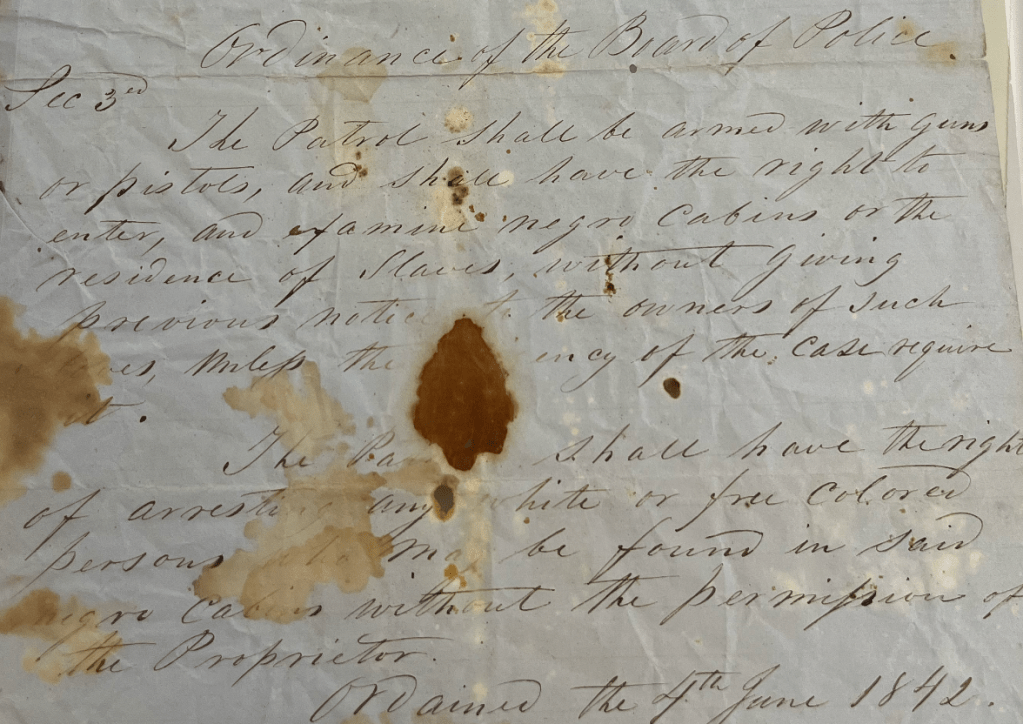

On 4 June, 1842, a new ordinance was passed permitting patrols to enter slave quarters unbeknownst to the enslaver, giving a thorough inspection of the quarters and being empowered to detain any white person or free person of color. Additionally, patrol officers were permitted to carry firearms, such as pistols, riffles, and likewise, into such quarters on the offset chance they were faced with resistance.

Mid-19th century marked a time of increasing subordination of enslaved people. While fugitive slaves were more harshly reprimanded for their attempted escape, receiving approximately twenty-five lashes, any contemplation of escape was subsequently challenged. Nonetheless, enslaved people attempted to run away to freedom in either the unsettled West or less stringent North. As the institution became more fragile, subsequent laws were enacted to combat the deterioration of slavery, becoming especially draconian throughout the American Civil War.

Policing during the Civil War

The American Civil War proved to be an existential time of crisis and panic regarding the institution of slavery. While enslaved people saw the war as a means of escaping bondage to a purportedly less discriminatory and free Union, enslavers dreaded the war as it threatened the very institution which upheld their wealth and livelihoods. To ensure enslaved people remained subordinated and were not successful in their journey toward the Union Army, the most egregious forms of restrictions were legislated in regards to slave patrols.

Much like the Black Code ordinances passed in 1806, enslaved people’s possessions, whereabouts, and actions were heavily regulated. However, nearly 60 years later, the Civil War restricted all aspects of enslaved people’s lives, condensing the already minuscule amount of sovereignty allotted to enslaved people. Out of fear of retaliation and aiding the Union Army, slave patrols were permitted to detain any enslaved person found working outside their respective plantation without the accompaniment of a white person. Moreover, if an enslaved person was found outside the premise of their enslaver’s plantation after nine O’clock, they were required to carry a pass which stated “the object of his errand, the hour and date of his departure, and return.” The specified revisions purposely made it increasingly more difficult for enslaved people to escape to the lines of the Union Army. Juxtaposed to the ordinances passed in 1806, the new ordinances passed in 1862 considered the avenues enslaved people would used to escape, such as forged passes or urban marronage, and concentrated on restricting said avenues.

Other ordinances heavily controlling the autonomy of enslaved people prohibited the assemblage of slaves outside of the plantation of their respective owner. Additionally, the owner would be permitted to pay a fine “of not less than twenty-five nor more than one hundred dollars.” The last provision likely provided incentive for enslavers to more stringently oversee their slaves and prevent the likelihood of insurrection. Generally, enslaved people were not authorized any autonomy. However, by the 1860s, they were expected to be supervised without surcease and were only permitted to the land of their enslavers.

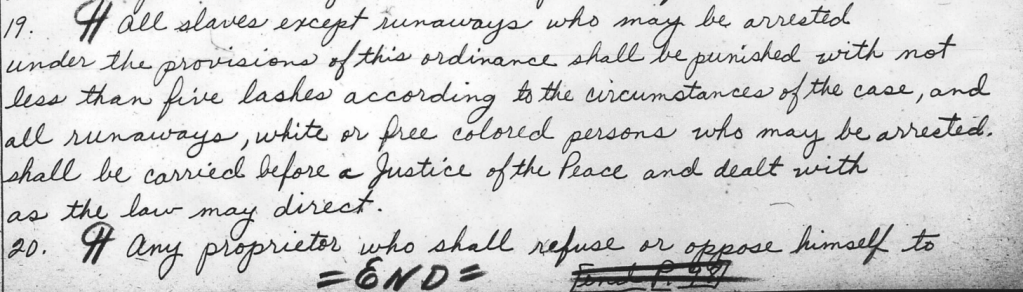

These provisions heavily repressing enslaved people were enacted in an attempt to deter notions of running away. By the time of the Civil War, with promise of emancipation or less strenuous provisions in the Northern states, fugitive slaves became more rampant. Thus, ordinances permitted draconian punishments, such as whippings, towards any slaves arrested under the aforementioned provisions. As for runaway slaves, punishments were left to be “dealt with as the law may direct.” This suggested a number of punishments fugitive slaves would be subjected to, some potentially losing their lives for a chance at freedom.

Contrastingly, ordinances pertaining to the slave patrols became slightly more flexible in its operations. As opposed to the initial patrolling acts of 1822, slave patrols began to require all white male inhabitants aged sixteen to sixty to participate in active patrolling duty rather than sixteen to fifty. Seemingly, the West Baton Rouge Police Jury believed extending the cut-off ten more years would allow for more effective patrols. Additionally, ordinances allowed leeway for the amount of men set out during patrols. “The Chief of Police is hereby empowered to hire a sufficient number of men to compose a permanent guard, not to exceed twenty men.” While the original ordinance permitted a total of five men per patrol, the revised act was subsequent of the Civil War, alluding to the panic which emerged as slavery was threatened. Finally, specified time was allotted to patrols in previous ordinances. However, during the Civil War “captains of the respective Wards shall have the power to vary said hours…. provided that no patrol shall do service for a less period than three hours adopted.” The revised provision allowed for flexibility, allowing patrols to more effective achieve its goals of deterring and capturing run away slaves. While panic and fear aided and abetting the enhancement of patrol laws, the Civil War provided the most stringent and fear-ridden provisions enacted thus far.

Conclusion

The institution of slavery was fragile, with mere manumission and escape threatening its very foundation. To combat any conception of running away, white enslavers promoted laws which were later enacted to uphold their preferred institution. While these laws provided framework for order and control of enslaved people in accordance with their enslavers’ wishes, one may wonder how these laws effected enslaved people themselves.

Although there is not much documentation to attest to the emotions these ordinances provided to enslaved people, one can speculate. The same anxieties of retaliation and revenge which fostered the enactment of such stringent laws were unanimously shared amongst the enslaved populations. However, the motivations for the anxieties differed. Enslaved people feared being reprimanded for their resistance by running away. Nevertheless, when the opportunity presented itself, they attempted to seize their freedom despite laws hindering the very action.

Slaves like Jane risked everything by running away. While each time attested to a different obstacle, the risk of freedom was nevertheless perpetual. In 1806, enslaved people were governed under similar laws instituted prior to the Louisiana Purchase. However, as they began to grapple with the chains that bound them to plantations, laws were enacted to fasten those chains.

By 1820, avenues for escape were egregiously blocked through the burgeoning police force all in an attempt to deter insurrection and further profit from the institution of slavery. By 1844, Jane attempted to flee. At this point in Baton Rouge, patrols were much more organized and stringent than its rudimentary counterparts. Nonetheless, Jane persevered, proving the exigent laws passed to suppress her movement were as futile as the institution she was likely born into. By 1860, many more enslaved people experienced a similar feat, acquiring freedom despite all odds being against them.

Despite the number of successful fleeing attempts, the subordination of enslaved people was successful, too. As the institution of slavery was rebranded into Black Codes, Jim Crow, segregation, and mass insurrection, the institution of patrols was, too, rebranded into modern day policing. While patrols eventually evolved into what we know as the police department to establish peace amongst all citizens, the deeply rooted racism of its origin nevertheless prevails.

Sources:

Arden, D.D., D.D. Arden Letter, Folder 1, Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections, Louisiana State University Special Collections.

Barnes, Rhae L. n.d. “America’s Largest Slave Revolt.” US History Scene. https://ushistoryscene.com/article/german-coast-uprising/.

Baton Rouge Gazette. 1860. “Project of a Code with Regard to Patrols in and for the Parish of Pointe Coupee.” Pointe Coupee Democrat (Pointe Coupee), November 17, 1860, 2. https://louisianastateuniversity-newspapers-com.libezp.lib.lsu.edu/image/354099855/?match=1&terms=patrols%3B%20article%201.

Breen, Patrick H. 2020. “Nat Turner’s Revolt (1831).” Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/turners-revolt-nat-1831/.

East Baton Rouge Parish (La.). Police Jury, 1827-1928, reel 153-172, Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections, Louisiana State University Special Collections.

First Legislature of the Territory of Orleans. 1806. “Acts Passed at the First Session of the First Legislature of the Territory of Orleans.” HathiTrust. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.35112203962842&seq=7.

Henderson, Stephen. 1844. “Ten Dollars Reward.” Baton-Rouge Gazette (Baton Rouge), May 18, 1844, 2. https://louisianastateuniversity-newspapers-com.libezp.lib.lsu.edu/image/319263555/?match=1&terms=slave%3B%20stephen%20henderson.

Louisiana Militia Saint Tammany Regiment, Saint Tammany Parish Militia Slave Patrol Order, March 29, 1862, Folder 1,, Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections, Louisiana State University Special Collections.

Louisiana State Gazette. 1823. “A Serious Subject.” June 26, 1823, 2. https://louisianastateuniversity-newspapers-com.libezp.lib.lsu.edu/image/282992039/?match=1&terms=patrol%3B%20swamp.

Martinez, Amanda. 2020. “Slavery during the Civil War.” Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/slavery-during-the-civil-war/.

Reid, John. 1822. “An Ordinance.” Baton-Rouge Gazette (Baton Rouge), October 12, 1822, 1. https://louisianastateuniversity-newspapers-com.libezp.lib.lsu.edu/image/253049901/?match=1&terms=an%20ordinance.

Weimer, Gregory K. 2015. “Policing Slavery: Order and the Development of Early Nineteenth-Century New Orleans and Salvador.” FIU Digital Commons. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3233&context=etd.

West Baton Rouge Parish (La.). Police Jury, 1858-1937, reel 560-564, Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections, Louisiana State University Special Collections.