by Dawson Lanclos

The story of a communal struggle for freedom and one man’s journey to find it.

You may have heard the phrase, “History is written by the victors.” The implications of this statement are vast. The idea that our modern understanding of the past is based entirely on who happened to come out on top adds a layer of skepticism where there was once certainty. In the modern age, there has been a shift to try and understand those on the bottom; those who were dominated and damned to be forgotten. This is one of those stories. Imagine for your entire life, you were defined not by your characteristics, your accomplishments, or even your family. Rather, your entire identity is attached to whoever owned you. Would you resist? Would you sacrifice everything just to taste one drop of freedom before you die? And if you failed, the government, the media, and the general population would drag your name through the mud until all that was left of your existence was shame, ridicule, and thin records of your failure. This is the story of the forgotten Lafayette slave revolt, but it’s also the story of a man on the bottom. A man who sacrificed his family and eventually his life in pursuit of one thing everyone can relate to: true liberty.

The Revolt

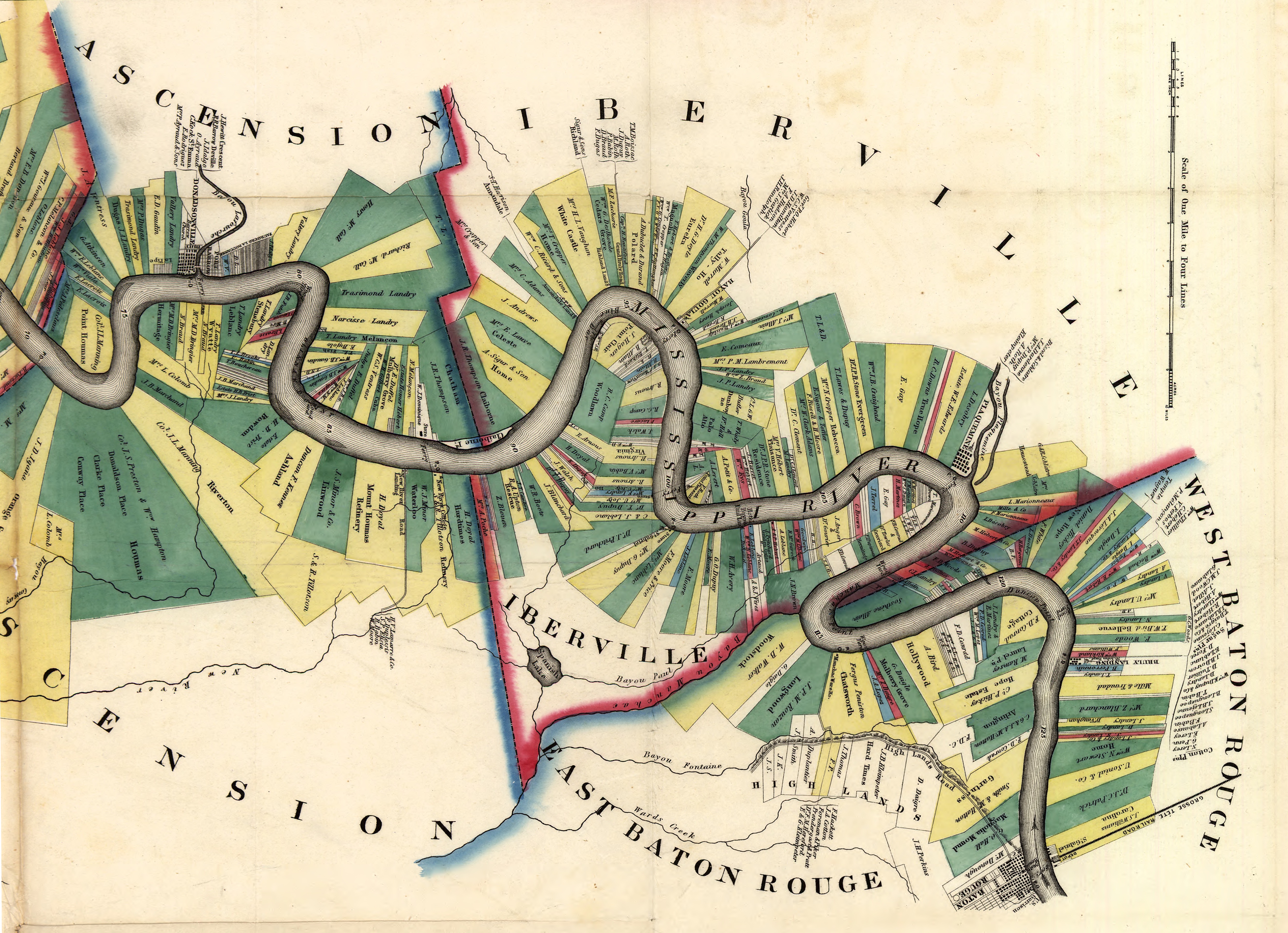

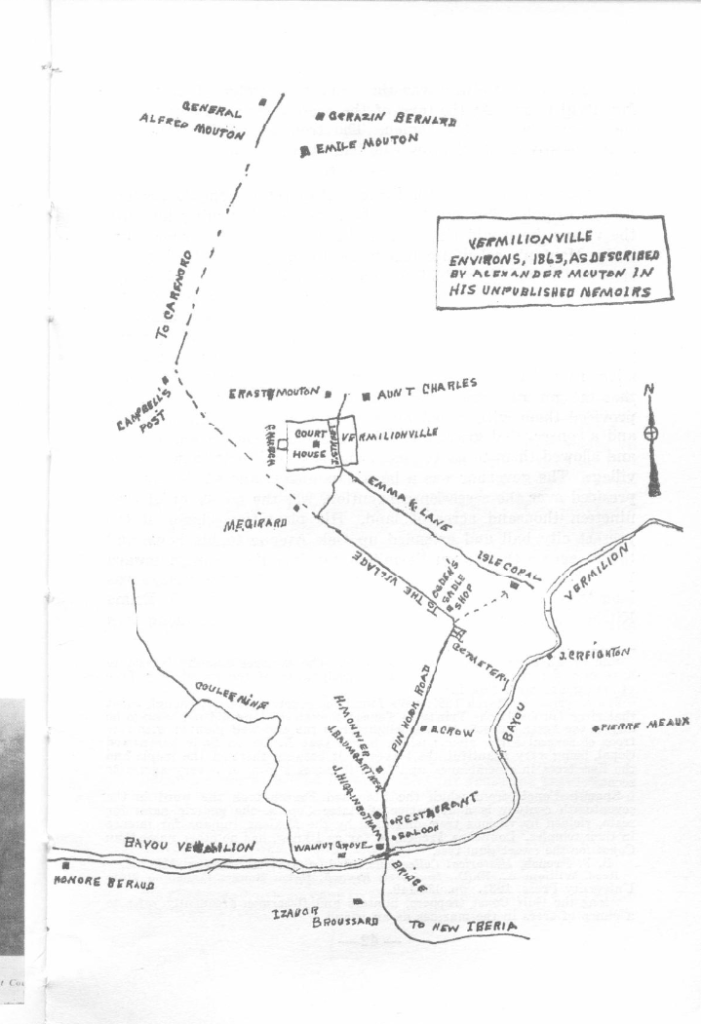

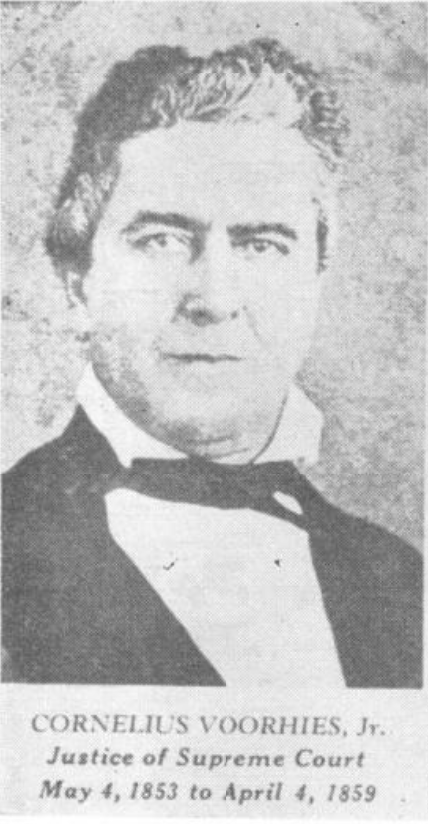

On Friday, August 28th, 1840, an enslaved man belonging to one Mr. Mercier exposes (or is forced to) a plot for an impending slave insurrection. The plan was this: on the evening of Saturday, August 29th, the enslaved people on the Plantation of Jacque Dupre would break out in revolt. They would use weapons being supplied to them by several white abolitionists and one man of mixed background. Among these weapons was a stolen cannon stashed in the woods outside of Lafayette. The ringleaders were also said to be enslaved people of the plantations of Mr. Cesaire Mouton, Mr. Cornelius Voorhies, Ms. Guilbeau, Ms. Meyer, and Mr. Neraud. After these plantations were captured, the liberated army would then meet behind the plantation of a man named Valerie D. Martin. The force of around 400 would then take up arms and march on the City of Lafayette (called Vermillionville at the time). After securing the city and likely growing their arsenal and manpower, they would split up: one group marching North to Opelousas, and the other heading East to St. Martinsville.

This plan, which sounds like the plot of an action movie, never took place. As soon as Mr. Mercier heard the plot, he immediately sent for the Sheriff. Upon hearing news of the impending insurrection, he arrested several enslaved people who had reportedly been a part of the plot. They were brought before a committee of “nine respectable inhabitants” (Baton Rouge Gazette, Sep. 12, 1840) and examined. The information gained by the Respectable Committee led to the arrest of twenty enslaved people, of which twelve were identified as involved. Of the twelve, nine were sentenced to death and hanged at their respective plantations. The remaining 3 managed to escape arrest. These men were named Jean (or John) Louis, Don Louis, and Henry. They managed to escape into the wetlands of the Atchafalaya Basin, where they would seek to live in seclusion, as free as they possibly could.

The Ballad of Jean Louis

At the time of the revolt Jean Louis, Don Lewis, and Henry were claimed to be owned by Cornelius Voorhees, Cesaire Mouton, and Mr. Neraud, respectively. At one time, Jean Louis was owned by Mr. Mouton along with his son Don, before the two were seemingly separated. We know that Jean Louis was once owned by Mr. Mouton because an accomplice to the revolt claimed that if they had succeeded, Jean Louis would return to whip his former master to death.

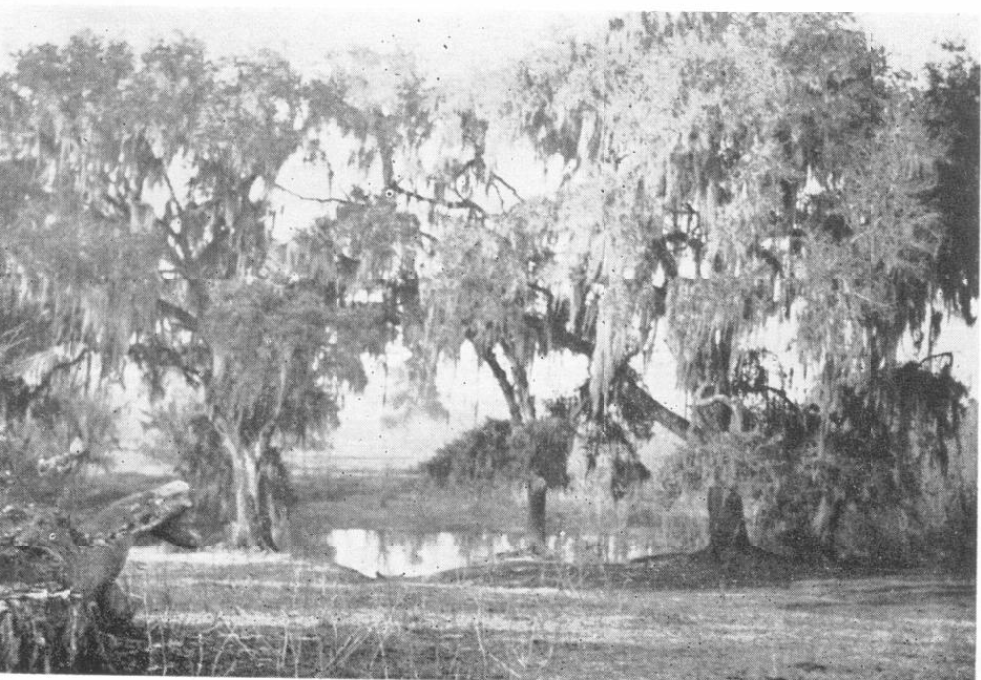

The three runaways were hiding out in a swamp called Bayou Chene, located in St. Martin Parish, just inside the Atchafalaya swamp. They remained there together for nearly a month before they were found. It is unclear exactly how they were located. The confrontation ended in the apprehension of Don Louis and Henry. Angry over the attempted revolt, the authorities thought it wasn’t enough to simply hang them. The bodies of Don Louis and Henry were dissected; their brains examined in the public square by one Dr. Buchanen. The newspapers continue to humiliate them even after death, saying, “They do not appear to have been at all remarkable.” Speaking on Don Louis, they say he was a “dull negro, possessing little or none of his father’s capacity or courage.” (Baton Rouge Gazette, Oct. 10, 1840) The anger of the journalists can be felt through their words as they insult these men who died for nothing more than their freedom.

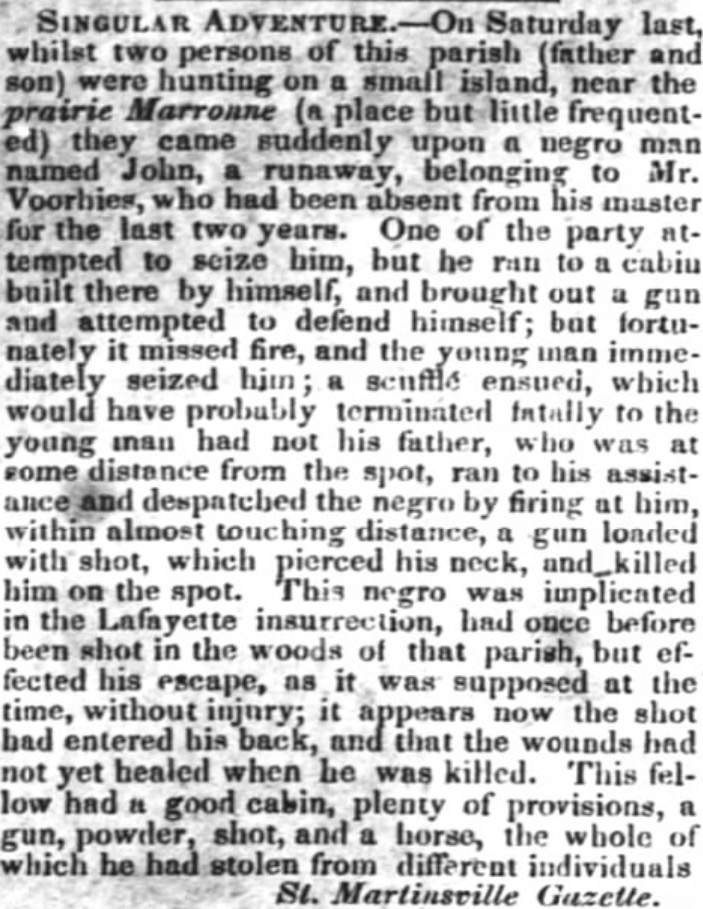

Jean Louis was now the sole survivor of the Lafayette Insurrection with a $300 bounty on his head. He had given up what little sense of security he had, his family, and any human contact. He would now spend the rest of his days secluded in the swamps of the Atchafalaya. He was in a place never meant for human habitation, be he still preferred it over living in chains. That is, until February 1841. Around four months after the death of his son, Jean Louis was killed by a pair of hunters who stumbled across his cabin. He was shot in the neck, “…within almost touching distance…” (Baton Rouge Times-Picayune Feb. 13, 1841) And with a single gunshot, the last living evidence of the Lafayette revolt from the other perspective was snuffed out.

Even though Jean Louis was seemingly dead, his name and dream lived on. In June of 1841, Jean Louis’ former master Cesaire Mouton was attacked by a white man with a knife. The attacker claimed he was there on behalf of Jean Louis. Mr. Mouton was able to subdue his attacker with the aid of a shotgun.

Why?

You may be asking yourself: Why is this story worth telling? At the end of the day, there was no revolt, only thwarted plans of one. My answer to that question is Jean Louis. Using nearly two-century-old newspapers and dusty books, a story was uncovered. The story of a man wrestling with a system designed to keep him subservient and inferior. I am certain that there are countless other stories like Jean Louis’. Deeply relatable stories of a single desire. A desire not tied to race, religion, or even nationality, but a shared desire of humanity: True liberty. Even within the scope of this single attempted revolt, there were dozens, if not hundreds, of other human beings who were willing to risk it all for freedom. Unfortunately, their stories may be lost to time. The ballad of Jean Louis is worth telling because through him, the lives, hopes, and dreams of these brave individuals live on. Through him, these people can claw their way back out from under the victors of history. So don’t forget the forgotten revolt, or the story of Jean Louis. Through your memory, the stories of hundreds live on despite the flow of time.

Sources:

Baton Rouge Gazette, Sep. 5, 1840

Baton Rouge Gazette, Sep. 8, 1840

Baton Rouge Gazette, Oct. 10, 1840

Baton Rouge Times-Picayune, Sep. 5, 1840,

Baton Rouge Times-Picayune, Feb. 13, 1841

Baton Rouge Times-Picayune, Jun. 13, 1841

Griffin, Harry Lewis. The Attakapas Country. Pelican Pub. Co, 1959.