by Jesse Dufour

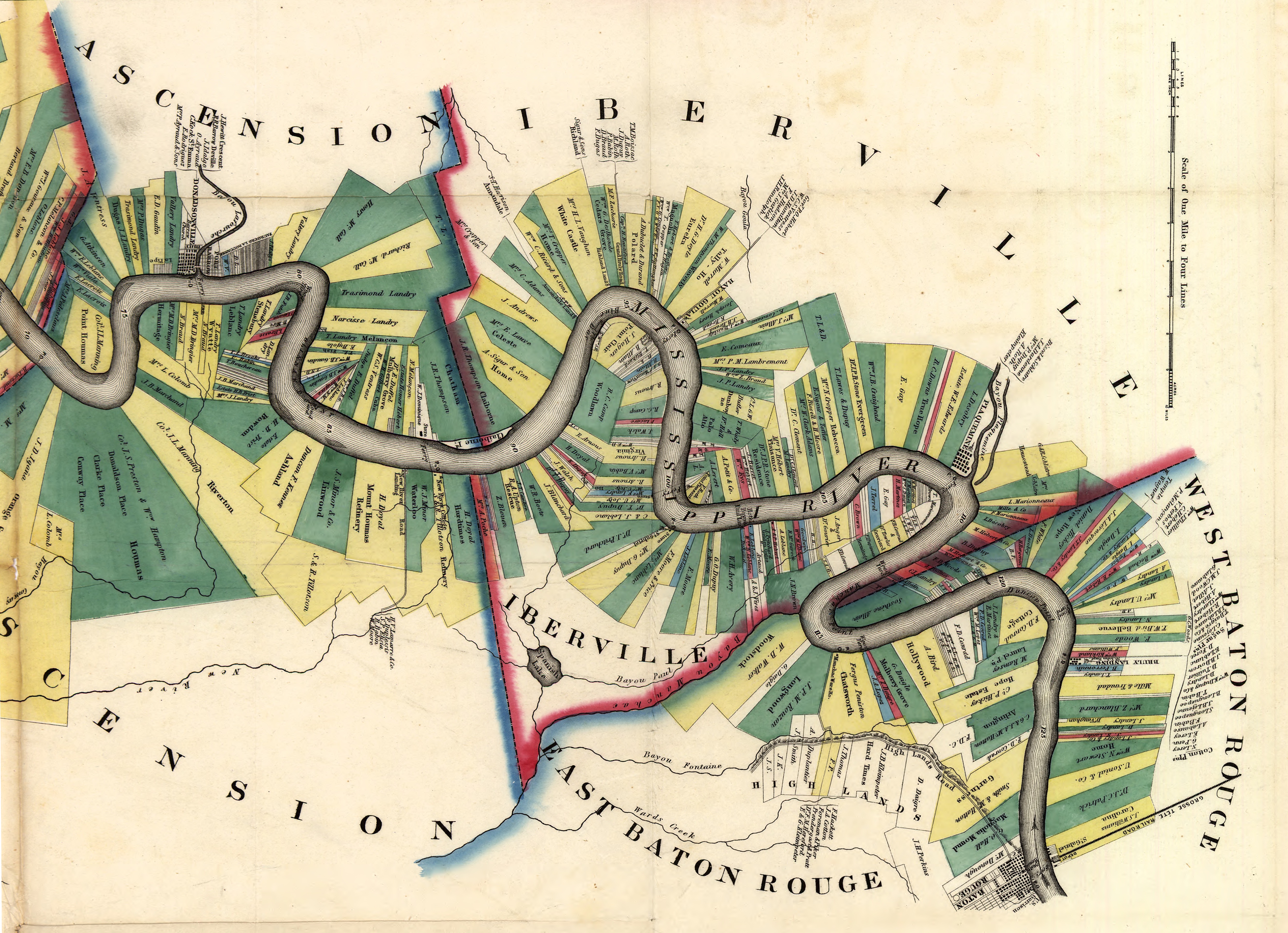

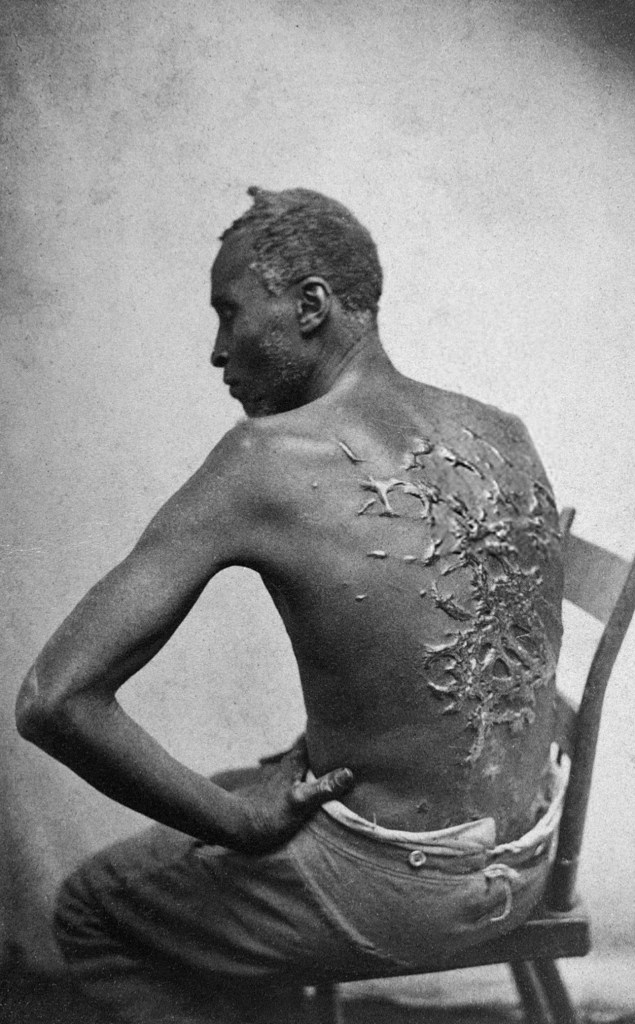

The first viral photograph was taken right here in Baton Rouge, Louisiana and featured the severely scourged back of an enslaved man. The Confiscation Act of 1862 allowed the Union army to designate runaway slaves as captives of war and grant them freedom. Many of these runaway slaves ultimately joined the Union army to fight against the very institution that had treated them as property for generations. One of these runaways while being examined by the medical staff in Baton Rouge, took his shirt off to reveal large welts on his back that he received after being brutally whipped by his overseer. A photograph was taken of this man’s back and was mass produced as carte de visites across the United States. To northerners, who were disconnected from the conflicts of the Civil War and slavery, this opened their eyes to the brutalities of slavery. To southerners, it was a fabricated story that hindered the nation’s view of what they described as a benevolent institution. The photograph became so popular that newspapers began writing articles about them. The most popular came from Harper’s Weekly four months after the photograph was taken.

The Harper’s Weekly Article

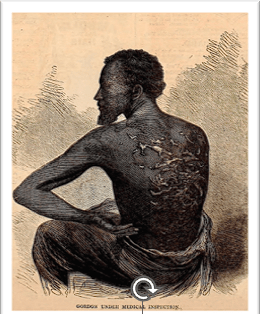

On July 4, 1863, Americans were met with these three harrowing woodcuts, seen below, in the new issue of the Harper’s Weekly newspaper. The issue describes that an enslaved man, named Gordon, had escaped from his master’s plantation and traversed swamps and bayous while being chased by blood hounds. The first woodcut portrays Gordon as he entered the Union camp in Baton Rouge. The second portrays Gordon undergoing the medical examination in the Union camp which revealed the unfathomable web of welts on his back, as stated before. The last portrays Gordon after he had enlisted into the Union army. Although this story is incredibly impactful, Harper’s Weekly did not get the story completely correct. An article written for the New York Daily Tribune has the most cohesive story of these three woodcuts. The article reveals that the three woodcuts featured in the Harper’s Weekly article were of three different men.

The New York Daily Tribune Article

On December 3, 1863, the New York Daily Tribune released an article explaining the true story of these three images. The article explains that on March 24, 1863, four enslaved men, belonging to Captain John Lyons and Louis Fabyan, escaped at around midnight. The four men were named as Peter, Gordon, John, and one unnamed man. The four men hoped to make it to Baton Rouge into Union territory. Then, on March 26, 1863, John ventured away from the party in search of food. Unfortunately, after an hour and a half of being gone, the party heard gunshots. Assuming John had either been captured or killed, the party moved forward. The party of three eventually made it to Union territory in Baton Rouge on April 2, 1863. The first woodcut featured in the Harper’s Weekly article is of the enslaved man named Gordon as he sits in a chair shortly after entering the Union camp. The actual photo of Gordon can be seen below (right). The second woodcut is of the enslaved man named Peter whose back was severely scared by his overseer. The actual photo of Peter can be seen below (left), as well. Contrary to the Harper’s Weekly article, the New York Daily Tribune offers a statement that is allegedly from Peter himself.

Peter’s Perspective

Peter’s narrative reveals very specific details about his life such as where he came from and who he was owned by. He explains that ten days from April 2, 1863, he and the four other men escaped from a plantation belonging to Captain John Lyons near Washington, Louisiana. When asked why he ran away from the plantation, he answered by ripping off his shirt revealing the severe scaring on his back. Soon after this, the famous photograph was taken. The very specific information provided by Peter in his narrative led me to pursue finding actual evidence of the purchase of either Peter or Gordon. I spent hours carefully examining records of slave sales archived at the St. Landry Parish Clerk of Court’s office. I found dozens of deeds of slave purchases made my John Lyons: surprisingly, none of those deeds referred to either a “Peter” or “Gordon.”

Conclusion

Although I could not find any record of Peter or Gordon in St. Landy Parish, their stories still can be significant to us. The story of Peter and Gordon challenge contemporary beliefs of Louisiana and shows that Baton Rouge was a haven for the enslaved to escape to. This was only possible due to the occupation of Union troops and the passing of the Confiscation Act of 1862. It also offers natives of Baton Rouge and the students at Louisiana State University a rich history for the city they grew up and went to college in. The first viral photograph was taken here, and more importantly, it was of an enslaved man. Lastly, the image shows perseverance in the face of an institution whose only goal is to exploit their unpaid labor.

Sources:

St. Landry Parish Clerk of Court, Conveyances year 1857 to 1858, February 12, 1855, Index to Conveyances A-Y 1805-1871, Familysearch.org

St. Landry Parish Clerk of Court, Conveyances year 1857 to 1858, April 13, 1857, Index to Conveyances A-Y 1805-1871, Familysearch.org

Harper’s Weekly, “A Typical Negro,” July 4, 1863

New York Daily Tribune, “The Realities of Slavery: ‘Poor Peter’” December 3, 1863