by Jacie L. Bellina

The Van Wickle Slave Smuggling Ring is a unique case of injustice and brutality. This particular case of slavery in southern Louisiana involves corruption, kidnapping, and the erasure of the lives and legacies of dozens of enslaved people. Research allows for valuable insight into this history as well as the possibility for some stories of the enslaved to be brought back to life.

The Van Wickle Slave Ring

The Gradual Abolition Act of 1804 started the process of phasing out slavery in the northern states. New Jersey implemented this act in 1812, and the Act freed the children of enslaved people born after July 3rd of that year. However, these children were not freed until they reached 21 and 25 years of age for women and men respectively. They remained in the service of their parent’s master during this time, but the idea was that this would eventually end slavery’s self-sustainability in these states.

The Gradual Abolition Act also greatly decreased the profitability of enslaved people in the north. The writing on the wall was clear for many northern planters: slavery was coming to an end for northern states. In response, New Jersey’s Middlesex County Court Judge Jacob Van Wickle created a slave smuggling ring comprised of a network of people between his home state and Louisiana. The Van Wickle Slave Ring was how he was able to maximize profit and retain power over enslaved people who would have otherwise been freed. It was not until the summer of 1818 that the people of New Jersey began to petition the state to stop the exportation of slaves out of the state. Many named the same man, Jacob Van Wickle, as noted in newspapers from the time.

Journey to Louisiana

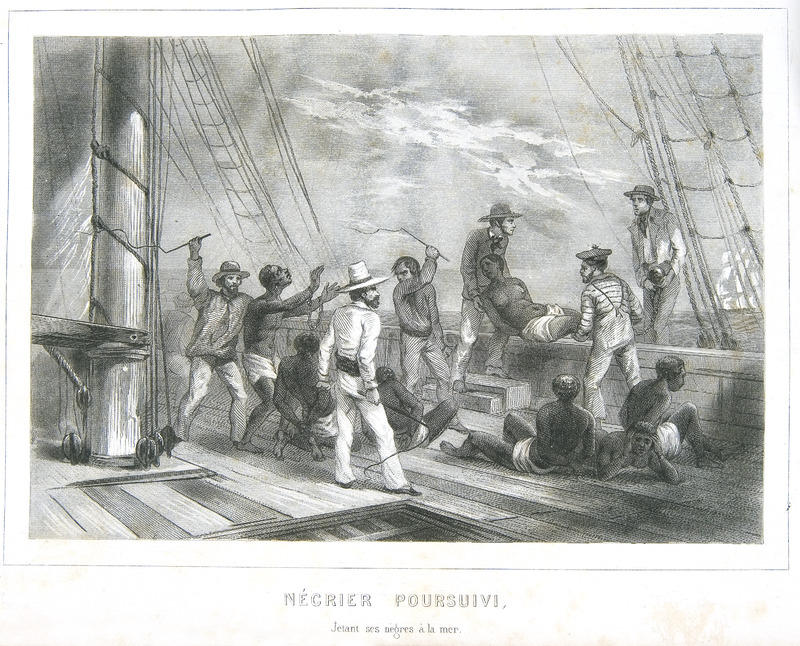

The slave ring operated from February until October of 1818, stealing the freedom of least 137 African Americans. Four different ships departed New Jersey in 1818: the Mary Ann in March, the Thorn in May, the Bliss in July, and the Schoharie in October. Dozens of people and their children were crowded into the unforgiving bilges of slave ships. The months-long journey consisted of suffocating heat and grim sanitary conditions. Newspapers report “The Slave Market” with a section on “New Jersey Blacks in New Orleans,” which records that 36 and 39 stolen slaves made it to New Orleans on the Mary-Ann and the Thorn, respectively.

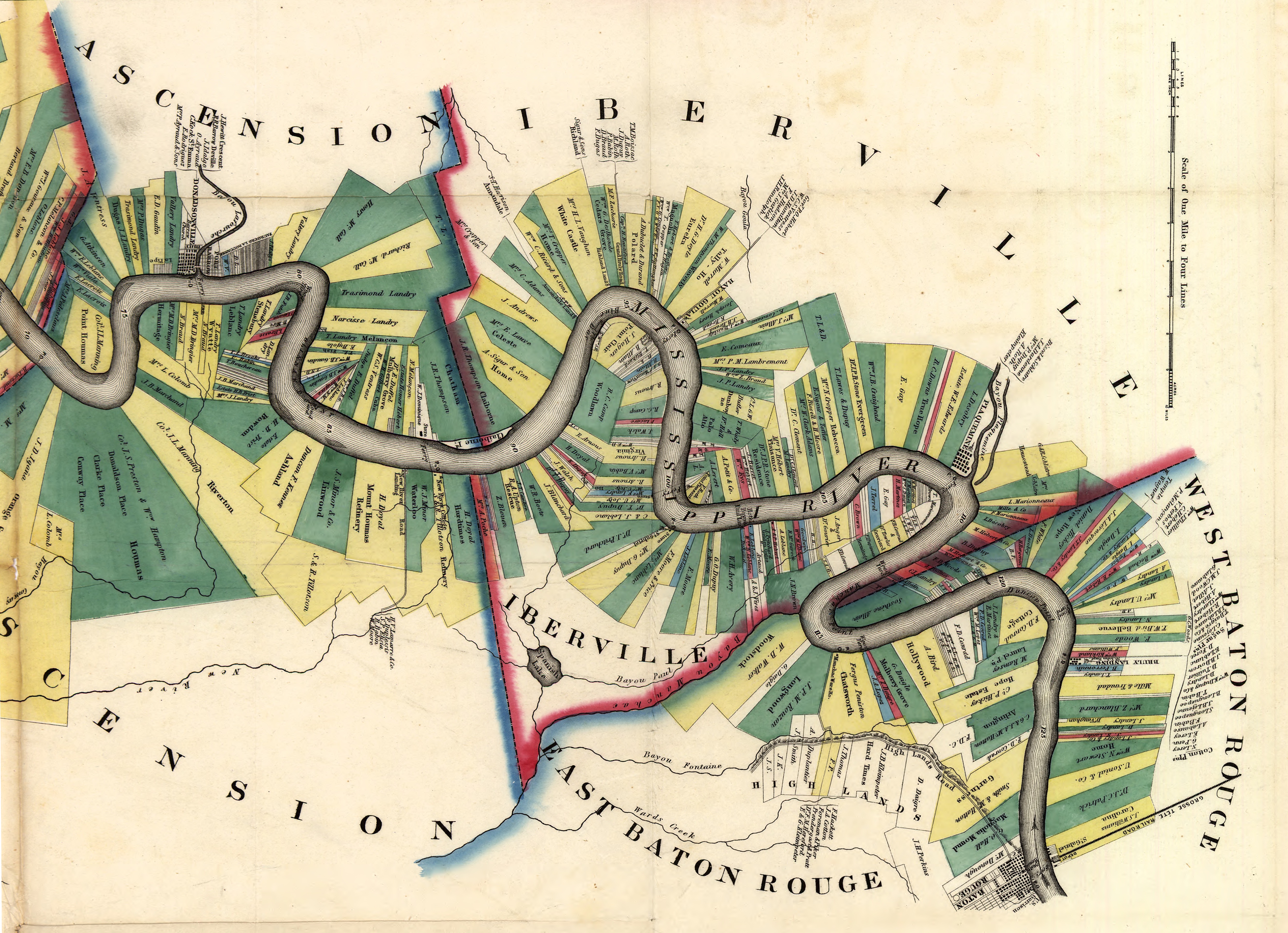

They disembarked in New Orleans, with many then being sent to Pointe Coupee parish. Nicholas, Jacob Van Wickle’s son, was the one who oversaw the physical “sale” of the enslaved people down south to Charles Morgan, Van Wickle’s brother-in-law. Since Morgan was married to Van Wickle’s sister, the enslaved people, and the wealth attached to them, remained in the consolidated control of the Morgan-Van Wickle families. With most going to Morgan, the enslaved ended up in Pointe Coupee parish on his plantation home, Morganza. Evidence also suggests that many slaves ended up in Concordia Parish as well as some found as far up the Mississippi River as Natchez, Mississippi. Over the following decades, the New Jersey enslaved are traded between family members, sold off to adjoining parishes, or in some cases, their fate remains a complete mystery.

The Stories of the Enslaved

Among the most heartbreaking aspects of this story is the promise of freedom for young lives that was never delivered on. Many children were taken by the slave ring because they were going to age out of slavery. The youngest recorded enslaved child was only a few weeks or days old when they were taken to Louisiana. Only a few children were fortunate enough to cling to their mothers aboard these ships, and the rest made the journey alone after being ripped away from their families and any familiar environment. Christeen was 27 years old when she was forced onto the Mary-Ann with her 9 and 2-year-old daughters, Diannah and Dorcas, in tow. Jacob, a 2-year-old boy made the journey with his mother Susan Silvey, and Samuel, also 2, went south with his mother Juda. 1-year olds, Susan and Hercules, were taken and sailed without any recorded family. Joseph, the youngest known victim of the Van Wickle slave ring was both born and taken in May of 1818, making him at most a few weeks old in the arms of his mother Nancy aboard the Thorn.

Despite the injustice, the brutal kidnapping, and the vicious cycle of slavery, this is a story of enduring human spirit in the face of a system dependent on the degradation of humanity. There is no end of justice or freedom for most of the people stolen from New Jersey, but in particular cases, the enslaved carved out a life for themselves against near insurmountable odds. Some slaves stayed in Morgan’s possession until the end of his life in 1848 and his estate inventory recorded the name, age, and appraisal of every slave. There are people within these documents who match the name and age of the slaves taken from New Jersey, giving reasonable confidence that these are the same people. Most importantly, Morgan’s estate mentions some familial relations of slaves, and the cases of Rosino (or Rosine), Rachel, and Caroline, stand out. Rosino was described as a “child” when she sailed on the Mary-Ann, and she is even recorded in a New Orleans Newspaper reporting the seizure of the Mary-Ann in June 1818. In 1848 she is married to a man named Jesse with an unnamed child. Rachel (or Rachael) was born in approximately 1796, and she was 22 years old when she was taken to Louisiana. In the estate inventory, she has a 3-year-old daughter named Isabelle. Finally, Caroline was born in 1800, making her about 18 years old when she sailed on the Thorn. By 1848, she is recorded as 50 years old and married to a man named Burnall.

Conclusion

It is essential that the disconnect in knowledge and advocation of this case be bridged. The Lost Soul Memorial Project in New Jersey has done crucial work researching the Van Wickle Slave Ring, but Louisiana lacks awareness of this story. Louisiana is as involved in this history as New Jersey, so it is imperative that the people of Louisiana gain an appropriate level of understanding as well. Additionally, what is most invaluable about this case is the different perspectives on slavery it provides. Awareness of the Van Wickle Slave Smuggling Ring proves that the injustices of slavery are not always contained to the “conventional” ways of thinking about it. This story contains not only the initial injustice of slavery but also the additional injustice of the enslaved being kidnapped when they would have otherwise been freed. Fortunately, with advocacy and further investigations, some justice or hopefully at the very least an acknowledgement of humanity can be brought to each and every victim.

Sources:

Bache, Richard. “Report of human trafficking in New Jersey.” Franklin Gazette, May 22, 1818.

Giantino, James. “Trading In Jersey Souls,” Pennsylvania History, Vol 77, no.3, 2010, 289-290, 292.

“The Slave Market – Report of New Jersey Blacks in New Orleans.” July, 1818. Morgan, Charles. “Morgan Estate Inventory.” 1848.

Rutgers University. “Removal to Louisiana: The Van Wickle Slave Ring.” https://scarletand

black.rutgers.edu/archive/exhibits/show/hub-city/removal-to-louisiana

Rutgers, Scarlet and Black Research Center, “New Jersey Slavery Records: Jacob Van Wickle (1770-1854).” https://records.njslavery.org/s/doc/item/1284