by Emma Thigpen

It is impossible to know how Mary, a woman who had spent her life held in slavery, would have felt as she realized she had a chance at freedom. We can never know if her heart fluttered with hope or if the shock of it made her heart race, if she felt trepidation knowing the system she would be going up against or bitterness toward the people who had deceived her and illegally held her in slavery. Either way, after the emotional revelation this must have evoked in her, Mary made a decision to do everything in her power to break the bonds tying herself and her children to slavery and fight for a life of freedom.

Background

When learning about the history of slavery, resistance is often taught in a way that defies the everyday struggle of people and centers around extraordinary circumstances. We learn about resilience in terms of individuals who survived insane circumstances and beat the odds. There is value in learning about large-scale rebellions and the Underground Railroad, but often, in pursuit of these stories, we forget the everyday individuals who lived their lives in our parishes. We neglect the people who fought for racial equality in our state specifically.

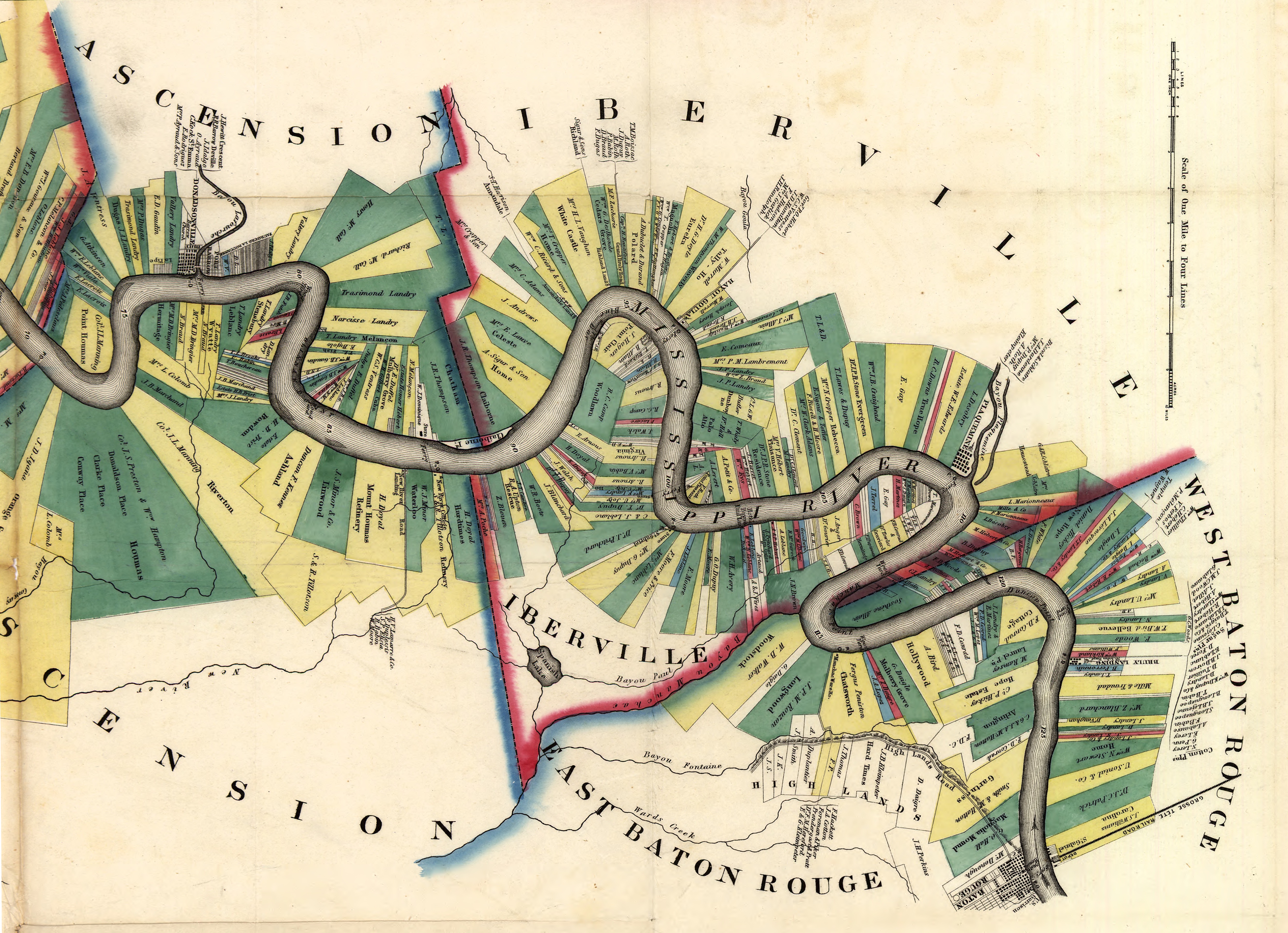

In Louisiana, slavery was woven into the fabric of being during the 18th and 19th centuries. It was a defining aspect of the social hierarchy, economic structure, and makeup of the legal system. As Louisiana changed hands from the French to the Spanish to American leadership, our state’s laws and customs were constantly changing which made navigating the laws about slavery difficult. Yet, in all three legal canons regarding slavery (The Code Noir passed in 1724, the Spanish Law put in place in 1764, and the Black Code of 1806), enslaved people were permitted to petition the state for freedom if they believed they had a valid case for it. What constitutes a valid case changed with every regime change, but what remained true is that when given the opportunity enslaved people in Louisiana displayed courage and determination to resist slavery and attempted to use the laws of the state to do so.

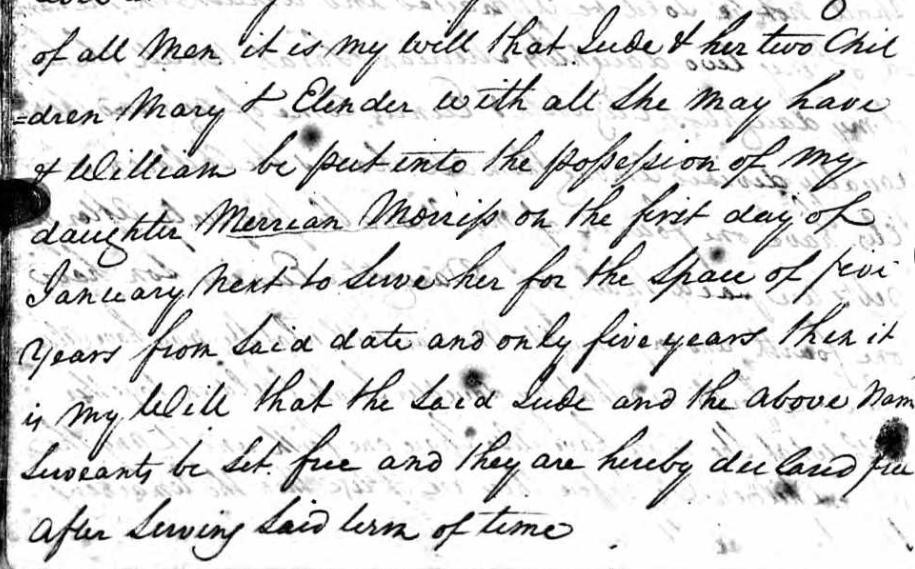

Emancipation petitions played a vital role in the process of freeing people from slavery before the Civil War. The duality of the legal system during this period is that it was both an active force in holding people in bondage and also an opportunity for enslaved people to free themselves. With dozens of cases every year, this avenue for resistance was a common way enslaved people could push back against an institution designed to take advantage of them. There are a couple of trends within the emancipation petitions — one of which is enslaved people who petitioned the state for freedom after their previous owners freed them in a will and testament. As enslaved people could not be freed at their owner’s discretion, the state had to approve every person transitioning from slavery to life as a free person of color. However, even if the owner’s wishes were perfectly clear, their wills were not always honored. In Mary’s case which we will get into below, her previous owner’s will was not honored for over a decade. The process included either an enslaved person or a free person petitioning and the court approving or denying said petition. If denied, often people would submit additional petitions until the court agreed to hear the case. These petitions were denied more often than they were approved, but in them, we can find rich stories of enslaved people dreaming and going after a life of freedom. In an area where individual stories have often been erased from history, these petitions recorded a wealth of information.

Mary’s Case

In the year 1815, a plantation owner named John Marshall signed and dated his final will and testament. Having written several over the years, it was evident he had gone back and forth about several of the clauses and had trouble deciding what to do with his enslaved people. But in the final copy, he wrote a statement that would set into motion a chain of events a decade later where Mary would have leverage to fight for her freedom. Shortly into the will, the statement reads, “believing that civil and religious liberty is the natural right of all men, it is my will that Jude and her two daughters be freed.” This sentence feels purposeful because he could have written that he wanted to free one of his enslaved people without the statement clarifying why. By specifying the reason was his belief in the natural rights of men, this case was clearly about freedom from its onset.

After Marshall’s death, most of his will was conducted quickly, but this clause and its ramifications were buried in a drawer to be left alone. Mary didn’t learn of this clause in the will until she had been forcibly moved from Georgia to Louisiana, had three additional children, and was sold to a different owner. The difficulty with studying slavery is that we don’t know much about Mary’s life before or after this took place. What Mary would have experienced or felt in those ten years before she learned about this or in the moment of realization is lost to history. Because this court case is the only written record of her, we must imagine what her life would have been like in this period. We do know that Mary was a mother of five who was provided a viable path to escaping slavery and decided to take it. She had to have known that petitioning the state was a risk as she would anger the plantation owner who fraudulently owned her, and there was a chance her petition would be denied. Despite these risks, when Mary learned of John Marshall’s intention and the neglect of its follow-through, she committed to doing everything she could to correct this deception.

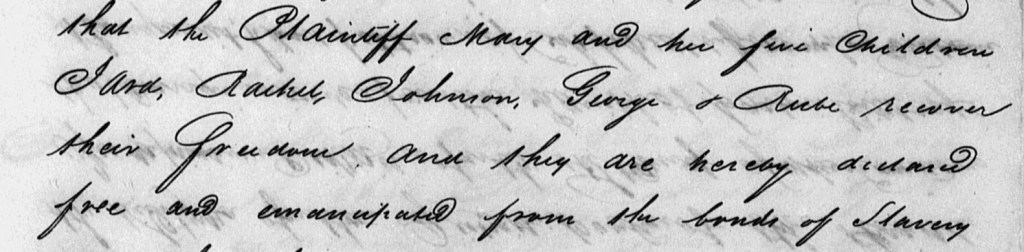

Mary’s first petition is dated to 1832 and accuses Miriam and Leroy Morris of “illegally and fraudulently” holding her in bondage and requests a sum of 2,000 dollars to pay back the wages they stole from her during the ten-year period her freedom was denied to her. This bold claim reads powerfully on the page as Mary lays out the injustices and inhumaneness of John Marshall’s family. This first petition is the first time Marshall’s will was brought to light and scrutinized. It feels powerful as the response reads out the names of Mary and her children. It says, “Mary the plaintiff in this will alleged to be a free woman of color with her five children: Jar aged nine years- Rachel and Robby aged about eight years- Johnson aged three years & George one year,” which tells us the names of people Mary was fighting for when she unburied John Marshall’s will.

When Mary’s petition moved through the judicial process, her case was eventually called before the Louisiana Supreme Court. Here she was able to submit several affidavits detailing her experiences, and her captor Leroy Morris was forced to appear and testify. There are several moments we know must have been emotional during the proceedings of the case. At one point, she submits an additional request for sequestration as she fears John Marshall will try to relocate her and silence her voice in their current jurisdiction. Her frustration and fear must have been difficult to bear, but she must have held onto hope as the document reads she “brought this suit to recover her liberty.” At another hard moment, she must request the court date be pushed back because a man meant to testify on her behalf was in New Orleans at the time. Once again, the subject of justice is brought up as the request declares the reason for a delay is the “furtherance of Justice.” What would she have been feeling as she wondered if this would break her case? Additionally, she had to request another sequestration of her young son Johnson who Mary feared was about to be sold by Leroy Morris. Mary must have felt relief as she and her children were taken into possession of the Sheriff instead of the man Leroy Morris whom she was actively pursuing a suit against. This court case is filled with elaborate and revealing documents — it includes testimonies written in affidavits, requests of the court, interrogations of people involved, and documentary evidence to enhance the case.

In the end, Mary’s courage to save herself and her children is rewarded. One of the final documents included in the case declares their right to freedom! Now upon hearing this, Mary could have been overwhelmed with joy and hope, relieved after five years of dealing with the legal system, or shocked that this was finally paying off. The Court declared, “the Plaintiff Mary and her five children Jar, Rachel, Johnson, George, and Robe recover their freedom and they are hereby declared free and emancipated from the bonds of slavery.” The conclusion of this case is an example of a time in our history when an enslaved person went up against people who had more social and financial capital and succeeded in gaining freedom for herself and her children.

Why It Matters

Individual Stories:

Mary’s story is important to learn for a multitude of reasons. One of which is that when learning about slavery, individual stories are powerful. Sometimes when we learn about this topic, we learn about the events in broad strokes, but it is impossible to comprehend the scale of injustice and tragedy until learning about the individual people facing these circumstances in our state. These are people who were forbidden from leaving their stories behind so what we do have is valuable. By going into detail about Mary’s life and her story, we are working against the dehumanization of enslaved people by the plantation class and remembering her as the human being she was. Instead of feeling separated from history and regarding it at a distance, learning the story of a mother who wanted to save herself and her family forces us to confront the emotional factor of uncovering people’s life stories. We are able to engage with a compassion for these people that is more difficult to fully lock onto when learning about slavery in general terms. Going beyond the general allows us to feel for this woman and remember her in a way the oppressive plantation owners never could have anticipated.

Local Heroes:

As mentioned, when we learn about slavery, we learn about exemplary figures who defied the odds and neglect to learn about the people in our state who fought for freedom on the same land we walk on today. These heroic figures who stood up to the system of the time are left untouched, and the power of their stories is not harnessed. But it is important to remember that people in our state were part of this fight, and enslaved people in Louisiana displayed courage and bravery in resisting enslavement. One way they did this is by filing emancipation petitions to pursue the freedom that was rightfully theirs. Similar to telling individual stories, thinking in terms of local heroes allows us to bridge this gap between ourselves and slavery and feel the connection this period has to our world today. We can feel awe as we learn the stories of the people who lived in our community and are woven into our history to resist bondage. Viewing Mary as a local hero allows us to remember these people who fought for freedom even if they weren’t remembered for it.

A Story of Resistance:

We often look for resistance in violence — we seek out stories of rebellions and an eye-for-an-eye pushback. But just as slavery was a part of every aspect of life in the 18th and 19th centuries, resistance was part of every aspect of enslaved people’s lives. They were constantly pushing back against a system that denied their humanity in infinitesimal ways that added up to something powerful. After a life of being enslaved, when Mary had the chance to escape slavery, she took it which disproves any paternalist ideas about enslaved people needing slavery. She asserted herself as a free woman and did not let her legal right to freedom be denied any longer. There is resistance in her actions as she shows her desire to escape this system and the injustices this system perpetuates. It is important when studying history that we view it through the lens of enslaved people in every public and private setting constantly in friction with their bondage.

Lasting Legacy:

This case is important to learn about for an endless number of reasons — standing witness to Mary’s bravery and denial of the system of slavery is powerful as we remember her as a local hero who fought for what she deserved and what her children deserved.

Source:

Mary f.w.c vs Leroy Morris, filed August 1832, Third District Court, East Baton Rouge Parish, “Slavery, Abolition, and Social Justice”