by Marandy Burrow

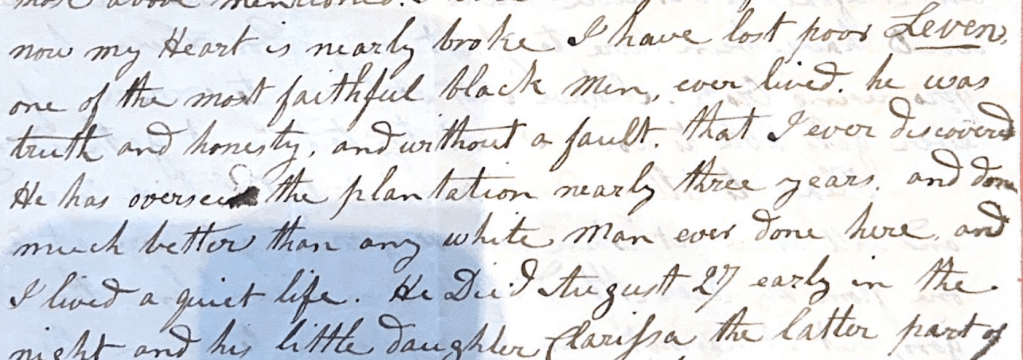

Leven Rock was the overseer of Evergreen Plantation from 1837 to his death in 1840. While it was routine for masters to hire overseers, Leven’s story is rare, primarily because of his enslaved status. Rachel O’Connor was the owner and manager of the plantation for the duration of Leven’s life and wrote letters detailing the activities of the plantation. These letters offer insight into the lives of the enlaved at Evergreen, particularly Leven. O’Connor’s letters and other documents provide details that can be used to reconstruct Leven’s life and offer readers a glimpse into the life of someone walking the line between the elite planter class and the enslaved community.

Overseers and Drivers in Louisiana

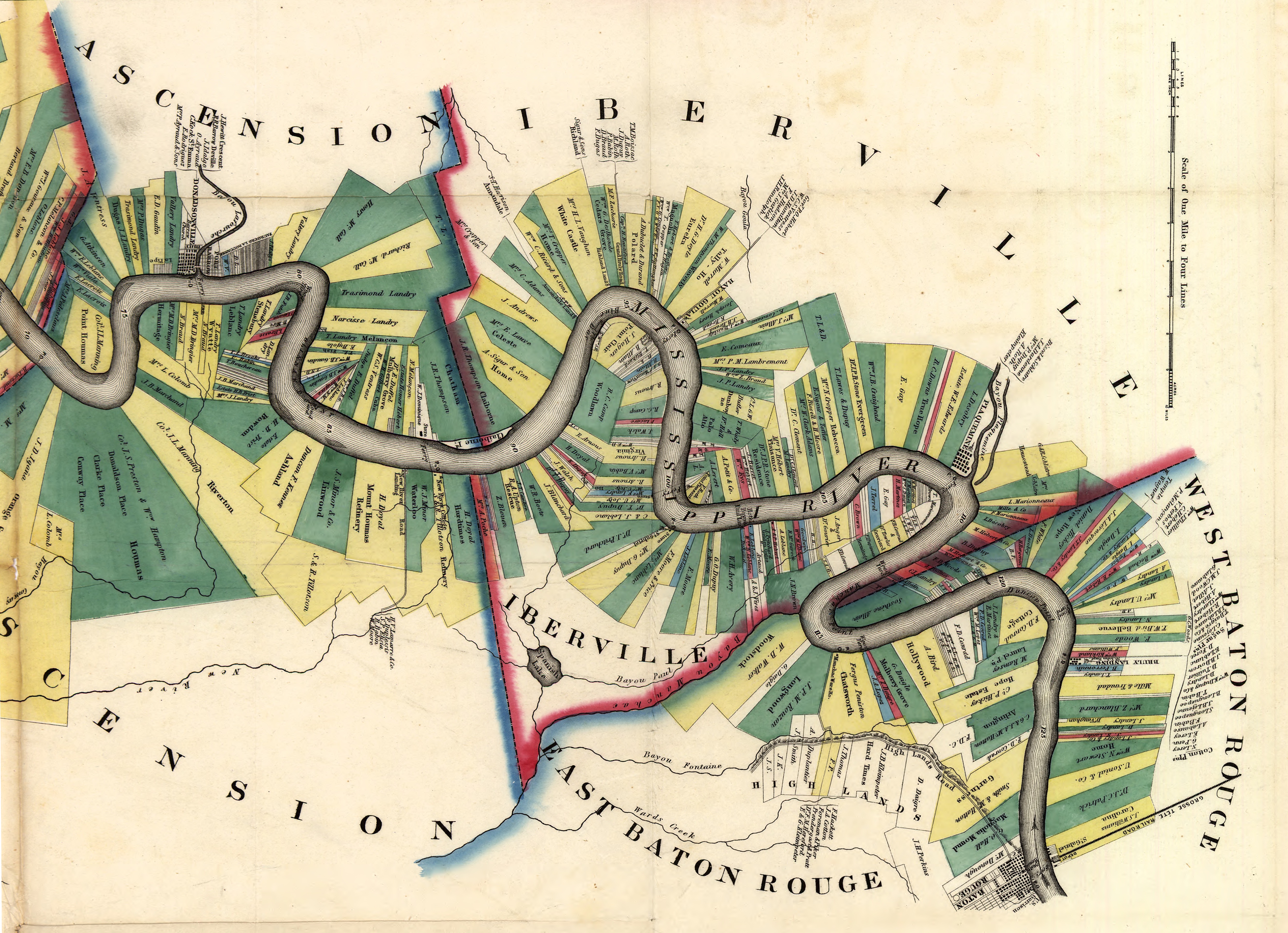

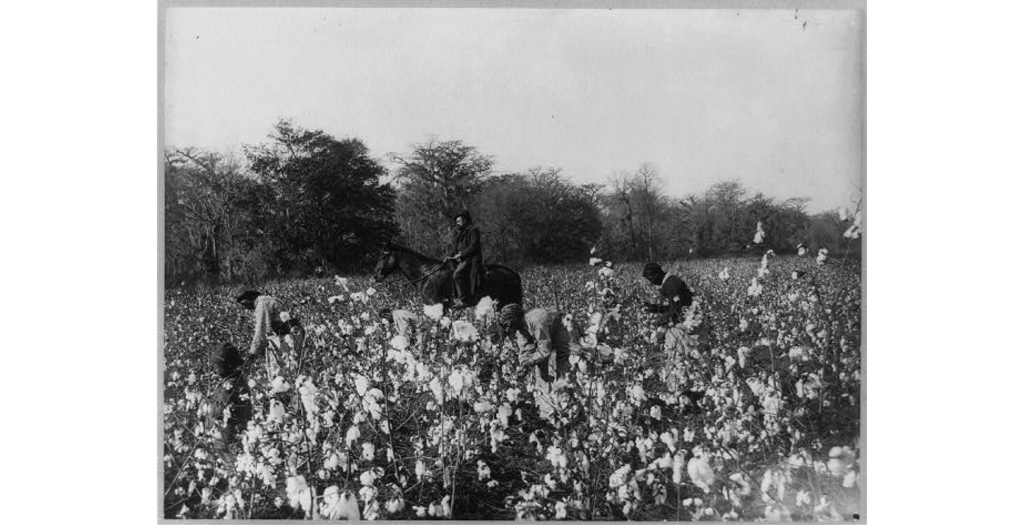

Most sizable plantations had at least one overseer who served as a middleman between plantation owners and enslaved people. Overseers were typically hired white men and held a social status between masters and non-slave-owning yeomen farmers. Their typical duties included directing the daily work of enslaved people, the discipline of the enlaved, the care of livestock and agriculture, and the production of the plantation’s crops. A plantation’s overseer was often viewed as directly responsible for the success or failure of the plantation, so the overseer took any steps necessary to ensure a machine-like operation. The overseer would do this by delegating tasks, assigning work gangs, and supervising field hands. Since enslaved people were classified as property, the overseer was also in charge of maintaining enslaveds’ health by providing medical services and ensuring they were fed and clean. This was not out of benevolence; the enlaved were seen as “cogs” within the plantation “machine,” and, as such, overseers had an economic incentive to sustain their physical health.

Drivers, while being enslaved themselves, took on a leadership role within plantations. They were managers of all enslaved field hands, tasked with keeping production high among the field hands. They served as foremen of the work gangs. Of the enslaved, they were widely regarded as the most important and knowledgeable concerning crop production and management. At times, drivers used corporal punishment to speed up production and eliminate disobedience. Drivers were placed in a particularly precarious position as they were often ostracized by other enslaved people because of their managerial status.

Leven Rock

In rare instances, enslaved men were promoted to the position of overseer. This was most common in plantations fully managed by widows. Female planters often preferred enslaved overseers because they could exact deference from them, whereas white overseers tended to disobey orders and disrespect female planters. With this in mind, and because of the abuse previous white overseers had taken out on enslaved people on the plantation, Rachel O’Connor promoted Leven to overseer in approximately 1837.

As with most of the enslaved population at Evergreen Plantation, Leven was born into slavery at Evergreen Plantation. His father Sam was likely one of the original enslaved people bought by the O’Connors between 1797 and 1810. Sam Rock was an integral part of the enslaved community at Evergreen Plantation. He was the “root” of the community – anchoring them to cultural values and providing support. Upon the relocation of Sam to David Weeks’ plantation in 1831, Leven was left “in charge” by his father. For the next few years, Leven had an informal leadership role in the community and attempted to fill the hole his father left. This might be another reason that Rachel O’Connor selected Leven to be overseer.

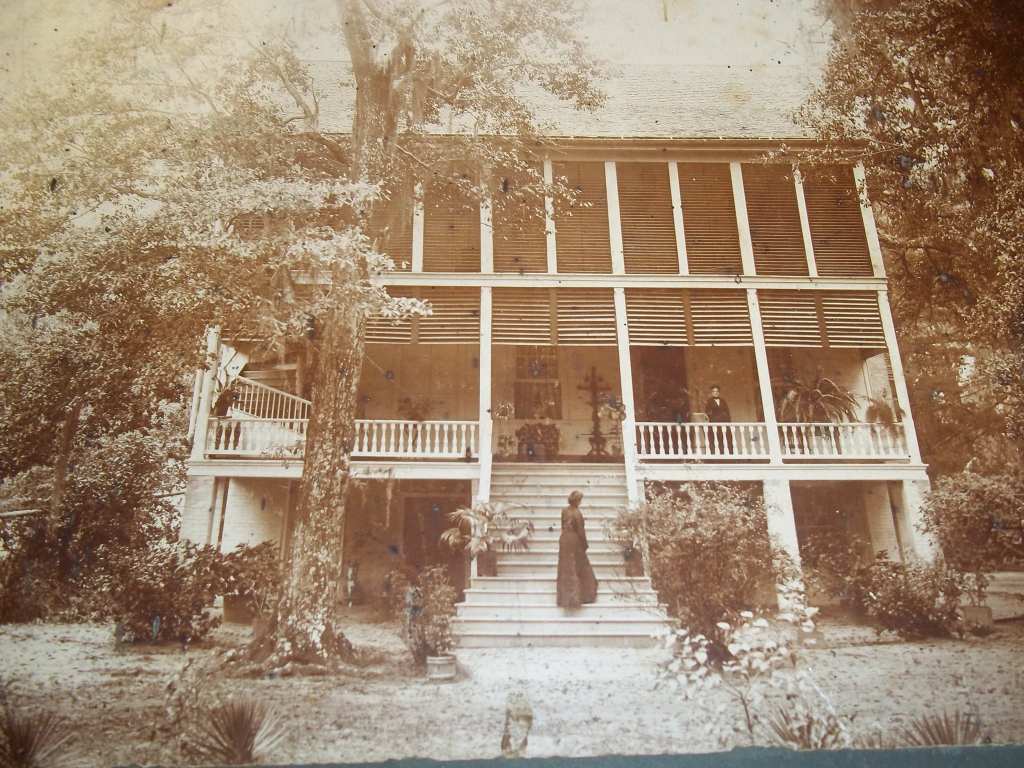

After shifting to the role of overseer, Leven’s life and daily tasks changed significantly. Leven and his family probably resided in the overseer’s house that was added to the property in the early 1800s. O’Connor’s letters provide clues about the day-to-day life of Leven. In a letter to her niece Frances in June 1840, O’Connor reveals that Leven has a gun in his possession, which he used to kill a wild turkey. Leven’s possession of a gun highlights both O’Connor’s trust in him and his status on the plantation. In a time when slave revolts were suspected or occurring often, a planter would have to have complete trust in an enslaved person to provide them with a weapon.

As an overseer, Leven’s effectiveness was directly tied to the production of the plantation, so he played a large role in its maintenance and success. After his death, O’Connor states that Leven left a promising crop. This was likely achieved through overseeing work in the fields, but it seems that Leven did not use extensive violence and abuse to motivate field hands, unlike past white overseers who were fired for their abuse of enslaved workers. Aside from overseeing production, Leven also performed managerial tasks, such as running errands to town or delivering messages for O’Connor. Additionally, he was likely very busy with keeping up with the health of the enslaved population as sickness devastated the plantation in the 1830s. While O’Connor expected her overseers to obey her orders exactly, she did appear to value Leven and his father Sam’s opinions on some level. Since the two were pillars of the enslaved community at Evergreen, O’Connor likely used them to connect with the community and keep it stabilized amidst a turbulent time in American history.

Conclusion

Leven’s story is unique and reveals critical details of enslaved family and community structures. Unlike in most masters’ and mistress’ accounts, Rachel O’Connor detailed the feelings of the enslaved, specifically when they lost family members and friends. Most of the letters mentioning Leven were written after his death, and it was apparent that his death violently shook the community at Evergreen Plantation. Leven’s elevated role on the plantation challenged the traditional power dynamics of the plantation system, and it is important to learn about unique stories like Leven’s to gain an understanding of the plantation system in Louisiana as a whole.

Sources

“Group of Negroes Picking Cotton.” Library of Congress, January 1, 1970. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3a14875/.

Malone, Ann Patton. Sweet chariot: Slave family and household structure in nineteenth-century Louisiana. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 1992.

“Oakley Plantation.” Great American Treasures, September 22, 2020. https://www.greatamericantreasures.org/destinations/oakley-plantation/.

O’Connor, Rachel Swayze, and Webb Allie Bayne Windham. Mistress of evergreen plantation: Rachel O’Connor’s legacy of letters, 1823-1845. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press, 1983.

Rachel O’Connor, Letter, September 4, 1840, Folder 62, Box 10, Slavery in Louisiana Collection, Louisiana State University Special Collections.

Sundberg, Sara Brooks, and Rachel O’Connor. “A Female Planter from West Feliciana Parish: The Letters of Rachel O’Connor.” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, Winter, 47, no. 1 (2006): 39–62.