by Harper Blakey and Camille Cronin

At the helm of Iberville Parish’s bustling plantation economy flowing on both Bayou Plaquemine and the Mississippi River, sat John Dutton. Planters controlled the river city’s economy through the proliferation of sugar and cotton on the backs of their human chattel, but John Dutton’s influence reached further than the four walls of his plantation on Bayou Plaquemine. Dutton’s dominant social status was built by his land and human ownership but was fortified by his judgeship. In his tenured decades as Iberville Parish’s judge during the Antebellum period, he decided on a vast number of slave trials despite his obvious bias as a slave owner himself. Unfortunately, such were the ways of the Antebellum South in the early to mid 1800’s and even today – money begets power. Wealthy men like John Dutton acquired political power from their plantation profits and used it to suppress rebellion and runaways and attempt to harm slaves through heinous punishments in slave trials to protect their precious South.

Judge Dutton’s Cases

An avenue to the protection of the plantation economy is Judge Dutton’s recurring cast of characters in his courtroom dramas like the Brown family and Captain Francis Duplesis. Wealthy planter families in the parish were able to play the parts of the plaintiff, the defendant, and the jury in different slave trials. The Browns are cited in numerous cases including one in 1820 where Josiah and Thomas Brown report another planter’s mistreatment of his slave, Amy. Another simple trial took place where one of their slaves went without paying a toll or receiving consent from Josiah Brown to ride on Thomas Brown’s boat. The Browns go behind the jury stand to sign off on the decision condemning two people for giving Joseph Erwin’s slaves liquor and onions from a flatboat on the Mississippi River. Capt. Francis Duplessis also enjoyed similar legal advantages in an 1830 case regarding his two children, Catharine and Alexander, whom he illegally possessed. The mother of the children was Mrs. Cabot Chessé who was a native of Haiti and a free woman of color but lacked the literacy to seek justice for Catherine and Alexander. Despite her illiteracy, Mrs. Chessé filed a complaint in the Orleans Parish Court to have her attorney, Edmund (also a free person of color), retrieve her precious children from Capt. Duplessis by a writ of Habeas Corpus. Without any consequence specified for Capt. Duplessis, the children were returned, where they would reside in New Orleans with their mother where their family would bear creative descendants of artists and puppeteers in the 1900s. Mrs. Chessé and her children were reunited, but Judge Dutton did not serve justice unto his great friend Capt. Duplessis. Though exciting in a courtroom drama, recurring powerful families are not compelling in an actual slave trial for the sake of collusion. The Browns and Francis Duplessis were always allowed a jury of their peers, literally.

In another case, a member of the Brown family decided the fate of a nonwhite “peer.” Jaques was a free man of color who was a slaveholder in Iberville Parish. In 1843, he filed with the parish court under John Dutton, that one slave belonging to him and the other belonging to his neighbor attempted to kill Jacques. In this case, the testimony of the slaves is shockingly read and used for judgment. John Dutton released the two slaves, finding them not guilty of attempted murder, and one of the slaves would continue to be owned by Jacques’. Free people of color in Louisiana were supposedly lavishing in legal and social rights, however, Jacques’ story reveals otherwise. Jacques’ wealth and even slave ownership were not enough to surmount the color of his skin in the eyes of the court in Iberville Parish. But, the true colors of Dutton’s Iberville Parish Court shine with an unignorable brightness during slave trials on alleged insurrections and violence against white slave owners.

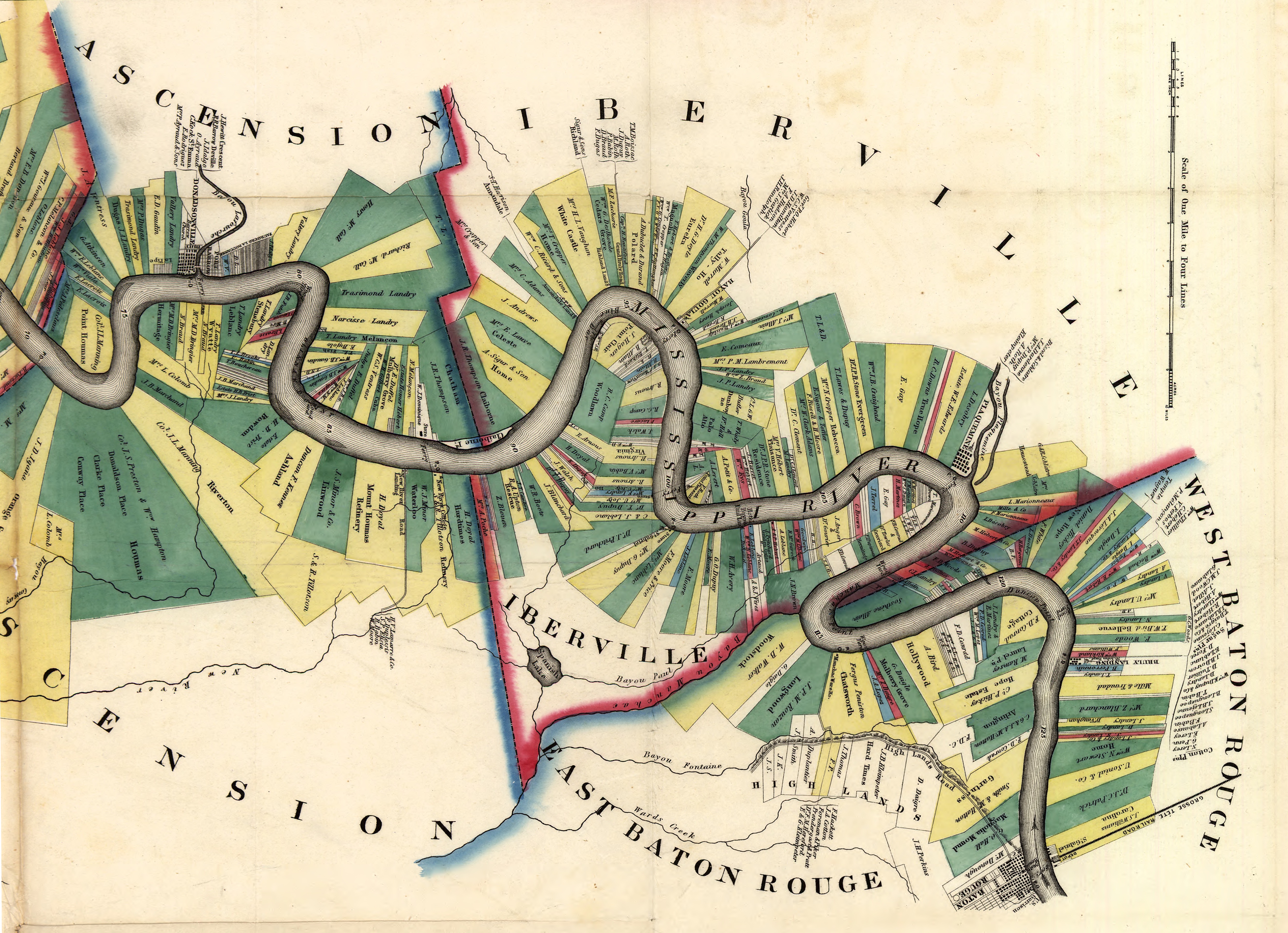

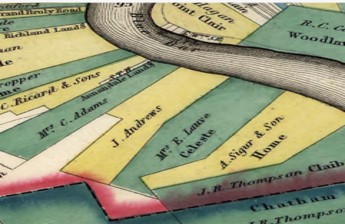

Judge Dutton and the jury of his white peers institutionally silenced slaves by prohibiting their rights to testify in most cases but still trying for a guilty or not guilty plea in cases of slaveholders’ blindly trusted accusations. Slaves Charlotte and Tom (of two different planters) felt the brunt of the forcefully discriminatory court when Judge Dutton punished their alleged threat of insurrection by hanging, an unfortunately usual form of capital punishment. Primus, a slave of a West Baton Rouge planter, however, did not fear Judge Dutton’s habitual violent punishments for insurrection. He was a frequent runaway, often participating in marronage, for even a taste of freedom. In an attempt to taste the freedom he craved, he pleaded not guilty on a charge of threatening to shoot two men to begin a slave revolt. Judge Dutton then mercilessly exacted the guilty verdict sentencing Primus to a violently cruel display of capital punishment: hanging between the Andrew and Lauve plantations and displaying Primus’ head on a pole on the levee.

In 1843, Joseph Schlatre brought charges against his slave Anthony for striking his son with an ax to which Anthony pleaded not guilty. Despite his not guilty plea, Judge Dutton and his band of jurors continued on their rampage of capital punishment. Anthony faced his own untimely, unjust, and inhumane death as it was forced upon him and remained utterly fearless in true “give me liberty or give me death” fashion.

The one-sidedness of cases in John Dutton’s court and other southern courts in this period exemplifies the violent legal silence for enslaved people both statutorily and personally enforced. Though enslaved individuals could plead guilty or not guilty, such pleas were disregarded as enslaved people were not allowed attorneys or the ability to understand court proceedings. Charlotte, Tom, Primus, and Anthony were not permitted to exist outside of oppressive court records and censuses classifying them by their status as owned individuals. While these slaves are not even listed with their full names and mere scraps of paper are left for historians to assemble their legacy, the Schlatre Plantation is privately owned today and featured in the Baton Rouge Advocate, and the Duplesis family’s car dealership has hundreds of vehicles branded with their name.

Lasting Impacts

Judges like John Dutton, and juries of wealthy white families like the Browns’, dismissing slaves’ legal rights further racialized the deprivation of due process that continued into the Jim Crow era and even bleeds through today. These slave trials give a sweeping view of the discriminatory legal system but also provide evidence for the inflammatory rhetoric that stokes persistent discrimination. For example, when slave attacks on Mr. Briddle were alleged in the case of Briddle v. Hudson, the testimony of Mr. Briddle included a statement reading, “Negros and slaves are…taking whites homes and wives.” John Dutton reviewed a litany of statements like this as legitimate evidence to sentence slaves to death. This legally supported rhetoric would later translate to the narratives that spurred white supremacist militias to lynch innocent black people in the 20th century. Slaves like Primus hanged for threatened insurrection by the legal system devolved into black men being lynched by white supremacists for empty allegations of raping white women.

Sources:

Blitzer, Carol Anne. “Cindy and John Hill Adapt a 200-Year-Old Plantation Home to Modern Living.” The Advocate, August 26, 2016. https://www.theadvocate.com/baton_rouge/entertainment_life/home_garden/cindy-and-john-hill-adapt-a-200-year-old-plantation-home-to-modern-living/article_1597a328-500e-11e6-a099-73978f1ff508.html.

“Execution of a Negro.” LOUIS: The Louisiana Library Network, The Daily Picayune (Times-Picayune) May 10, 1843. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libezp.lib.lsu.edu/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&sort=YMD_date%3AA&page=4&f=advanced&val-base-0=anthony&fld-base-0=ocrtext&bln-base-1=and&val-base-1=1843&fld-base-1=YMD_date&bln-base-2=and&val-base-2=louisiana+&fld-base-2=publocation&docref=image%2Fv2%3A1223BCE5B718A166%40EANX-1225C25F8DB53B48%402394331-1223D95A5FC15178%401-123A536192AA0AB3%40Execution%2BOf%2BA%2BNegro&firsthit=yes.

Garde Voir Ci. “Michael Schlatre.” Garde Voir Ci. Accessed December 4, 2023. https://gardevoirci.nicholls.edu/2020/michael-schlatre/.

Iberville Parish Civil Records, 1820-1846, Microfilm IV8.1, Criminal Court Records: Bills of Information (1820-1846), Louisiana State Archives.

Persac, Marie Adrien, Benjamin Moore Norman, and J.H. Colton & Co. Norman’s chart of the lower Mississippi River. New Orleans, B. M. Norman, 1858. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/78692178/.

“Runaway.” LOUIS: The Louisiana Library Network, The Daily Picayune (Times-Picayune), August 23, 1839. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.libezp.lib.lsu.edu/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&t=state%3ALA%21USA%2B-%2BLouisiana&sort=YMD_date%3AA&page=1&fld-nav-0=YMD_date&val-nav-0=1839+-+1841&fld-base-0=alltext&val-base-0=primus&val-database-0=&fld-database-0=database&docref=image%2Fv2%3A1223BCE5B718A166%40EANX-122423E255259AD0%402392975-1223CFC952FA1BC8%403-123BD3E75CC82ECA%40Advertisement&firsthit=yes.

Slave biographies. Accessed December 4, 2023. https://slavebiographies.org/search.php.

“United States Census, 1830”, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GYYN-3MML?view=index&action=view: Thu Oct 05 21:37:56 UTC 2023), Entry for John Dutton, 1840.

“United States Census, 1840”, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XHTD-SSZ : Thu Oct 05 21:37:56 UTC 2023), Entry for Joseph Schlatre, 1840.