by Jalen Pettus

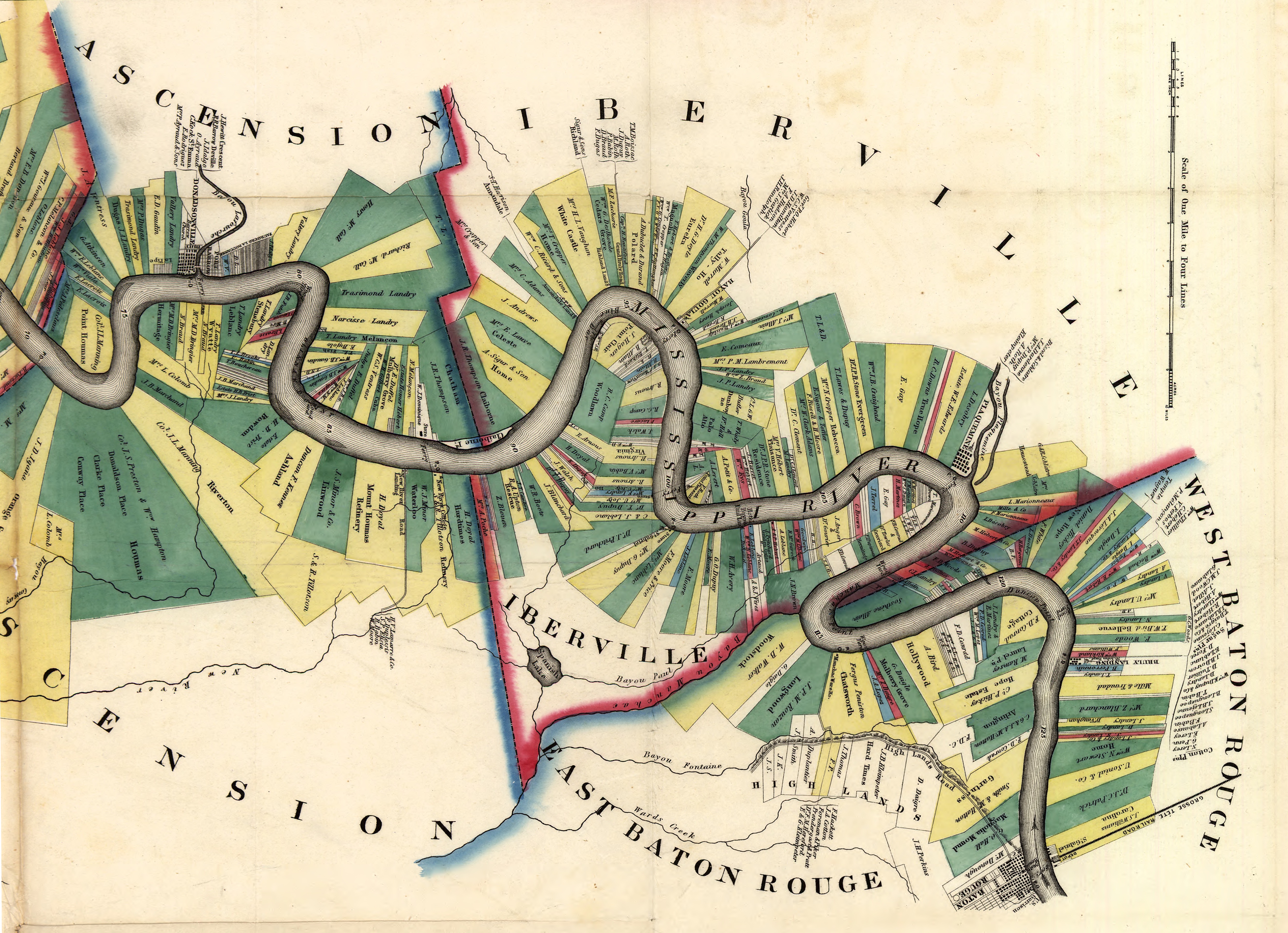

The City of Baton Rouge is a place teeming with history, largely unseen and largely unheard of. Despite being less prominent than its counterpart, New Orleans, Baton Rouge is no less significant to the development of Louisiana, from its humble beginnings as a French trading outpost to its place as the seat of government in the state. One facet of these largely unseen, largely unheard-of relics of the past is neither unseen nor unheard. It is used virtually every hour of every day by the thousands of commuters who travel on them in an almost circadian rhythm. This relic, of course, is the roadways of Baton Rouge. These roadways, including familiar names such as Highland Road, Plank Road, and River Road, are often not given a second thought concerning historical significance. More realistically, the only thoughts one may have about these roads are the state of disrepair they exist in or the annoyance of the traffic that plagues them at the 5 o’clock hour. These roads are much more, however, as they tell a very detailed and nuanced story of the history of Baton Rouge, from its colonial beginnings to its plantation-driven economy, and most importantly, the impact of the institution of slavery in the city and state at large. This begs the question: What impact did enslaved labor have on the development of the roads we drive on daily? Do we drive over the remnants of slave labor?

[subtitle 1]

Transcripts from the now-defunct East Baton Rouge Police Jury (which existed from the founding of the parish until the consolidation of the parish and city governments in 1949) provide a detailed insight into the answer to the question posed prior. Using transcripts of meeting minutes from 1859-1860, one can see that East Baton Rouge Parish undertook massive infrastructure projects that included the construction of roads. From further examination of the transcripts, one can also see that the parish actively engaged in the use of enslaved labor to construct these roads, requiring slaveholders to contract out their enslaved laborers to the parish in support of these public works projects. This includes some major roads that still exist in present-day Baton Rouge, perhaps some of the roads traveling through LSU.

The organization of this construction was subdivided into what the Police Jury called “road districts”. Within these districts, a resident of the parish was appointed overseer of the road project, appointed by the police jury to manage the enslaved laborers assigned to work on the road project, as well as the project’s progress. It is highly probable that the enslaved people constructing the roads endured grueling conditions at the hands of the appointed overseers, who had no personal stake in the severity of punishment if an enslaved person was deemed to be underperforming. This was not the extent of the police jury’s power however, they even selected the plantations from which the laborers would be acquired. Initially, only some “hands” (enslaved people) were required for the construction projects, however, this would change in September 1860, detailed in a proclamation by the police jury requiring that “all hands working in the field male and female shall be liable to road duty from and after this date.” This is likely the result of parish leaders seeing the writing on the wall concerning future conflict (The Civil War).

It is certainly a fair assumption that the police jury took its role in road construction quite seriously, as it was quite heavy-handed in the enforcement of its mandate. Meeting minutes from June of 1859 show that the city actively fined slaveholders whose hands were not present for work, stating that the “fine for hands not working the roads be and is hereby amended so as to make the fine five dollars and seventy-five cents.” Later meeting minutes also from September of 1860 show the police jury authorizing lawsuits by the city attorney against slave owners who failed to permit their hands to work road duty. It is clear from these measures that the policy was not popular, and understandably so as plantations would experience great losses in productivity, especially during all calls. This policy seems to have temporarily converted enslaved people who were owned by private owners into city property in a form that is almost similar to eminent domain. This would sow tension between the parish government and the planter class, who despised having to comply with the policy, as they suffered losses.

It is worth noting that the use of slave labor is not uncommon, as owners often contracted their enslaved laborers out to public works projects. Enslaved people are responsible for the construction of most of America’s most influential and important buildings and monuments, including the U.S. Capitol and the White House. In Louisiana, enslaved labor was responsible for the construction of much of the state’s infrastructure. “In New Orleans and Baton Rouge, essential public infrastructure was primarily built by chain gangs of imprisoned enslaved people taken from the cities’ slave jails.” It is, however, uncommon to see a local government require slave owners to contract out their “property” without obvious or express compensation, which the 5th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution stipulates.

[subtitle 2]

Plank Road is a prime example of a currently existing road built by enslaved people to service the plantation infrastructure. The history of Plank Road dates back to the 1850s when groundbreaking on the road was undertaken by enslaved laborers from Baton Rouge area plantations. The road came about as the result of plantation owners’ desires to streamline the exportation of goods such as cotton and sugarcane to a train depot in Clinton, LA. The road was aptly named “Plank Road” because it was constructed using wooden planks in its early construction stages, a building technique popular in the 1850s, viewed as a significant improvement from the dirt roads that would often turn into impassable mud during the heavy rains which are common to the region. One would be remiss not to mention the evolution of Plank Road, from affluent plantation land to a working-class majority-white neighborhood, to its dilapidated state that is now majority black, clearly reflecting the generational systemic inequality of the Antebellum plantation economy and Postbellum Jim Crow South.

Oftentimes when we examine the institution of slavery and its impact, we view this history through a tertiary lens. A perspective that recognizes the brutality of the institution and its impacts, but at a level that is seemingly shallow. It does not truly recognize how directly the labor and toils of thousands of unnamed and unheard enslaved people are responsible for our relative ease of life today. The impact of enslaved labor on today’s society without a doubt is profound and far-reaching, leaving an indelible mark on various aspects of our social, economic, and cultural fabric. It is certainly worth noting that the use of enslaved labor in constructing roads to support plantations forms a chilling juxtaposition with the persistent socioeconomic disparities seen in today’s society. The exploitation of these people laid the foundation for significant wealth accumulation among a privileged few, while the laborers and their descendants were denied basic human rights and subjected to dehumanizing conditions. The construction of roads, a symbol of economic prosperity, also serves as a metaphor for the enduring infrastructure of systemic inequality. Acknowledging this historical context is crucial for understanding the entrenched nature of current socioeconomic disparities and developing effective strategies to address and dismantle these systemic barriers. The juxtaposition of enslaved labor building roads for plantation economies with today’s disparities underscores the ongoing need for societal reflection, reparative action, and a commitment to creating a more just and equitable future, informed by our past.

Implications

Though Baton Rouge’s hidden road builders may be unnamed and unheard, unseen but always present, they will certainly not go on unrecognized. This is the purpose of this project and others like it; to shine light and provide a voice to those who are unable to do so themselves. To honor their legacies and recognize their long-lasting impact. To provide a commentary informed by research and personal experience. By recognizing and commemorating the contributions of the enslaved road builders, we pay homage to their endurance and fortitude. It is my sincere hope that through unveiling this “hidden history”, we can strive to create a path toward reconciliation, understanding, and a shared commitment to a better and more inclusive future for Baton Rouge.

Sources:

EBR Parish Police Jury, September 1860, Reel 156, W.P.A. Collection, LSU Special Collections

EBR Parish Police Jury, June 1859, Reel 156, W.P.A. Collection, LSU Special Collections

Bardes, John. “Urban Slavery in Antebellum Louisiana.” 64 Parishes, Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, 20 June 2023

“Imagine Plank Road: Plan for Equitable Development Final Report .” Build Baton Rouge, 7 Dec. 2020

Foster, Sheila, et al. “Understanding Plank Road: Part 1.” LabGov Georgetown, 2 Dec. 2019