By Emily Marionneaux

The antebellum period in South Louisiana was a period of growth — marked by expanding populations, rising wealth, and improvements in education — at least, that is, for wealthy, white people. This era of progress was built alongside, and deeply intertwined with, the enduring and oppressive institution of slavery. In 19th-century Louisiana, enslaved people were legally and economically categorized as property, routinely listed alongside livestock and tools in financial documents such as mortgages, wills, and probate inventories. Though they shared the same human characteristics as their enslavers, they were reduced to assets to be inherited, mortgaged, and sold. Today, it is hard for the 21st-century mind to comprehend this ownership mentality. However, using an example of a slave owning family in Iberville Parish, an examination of financial records, such as probate inventories and conveyance accounts, reveals the extent to which enslaved people were treated as economic assets.

The Enslaved People of the Cropper Family

Unfortunately, it is impossible to discuss enslaved people in the antebellum era without reference to the individuals who enslaved them.

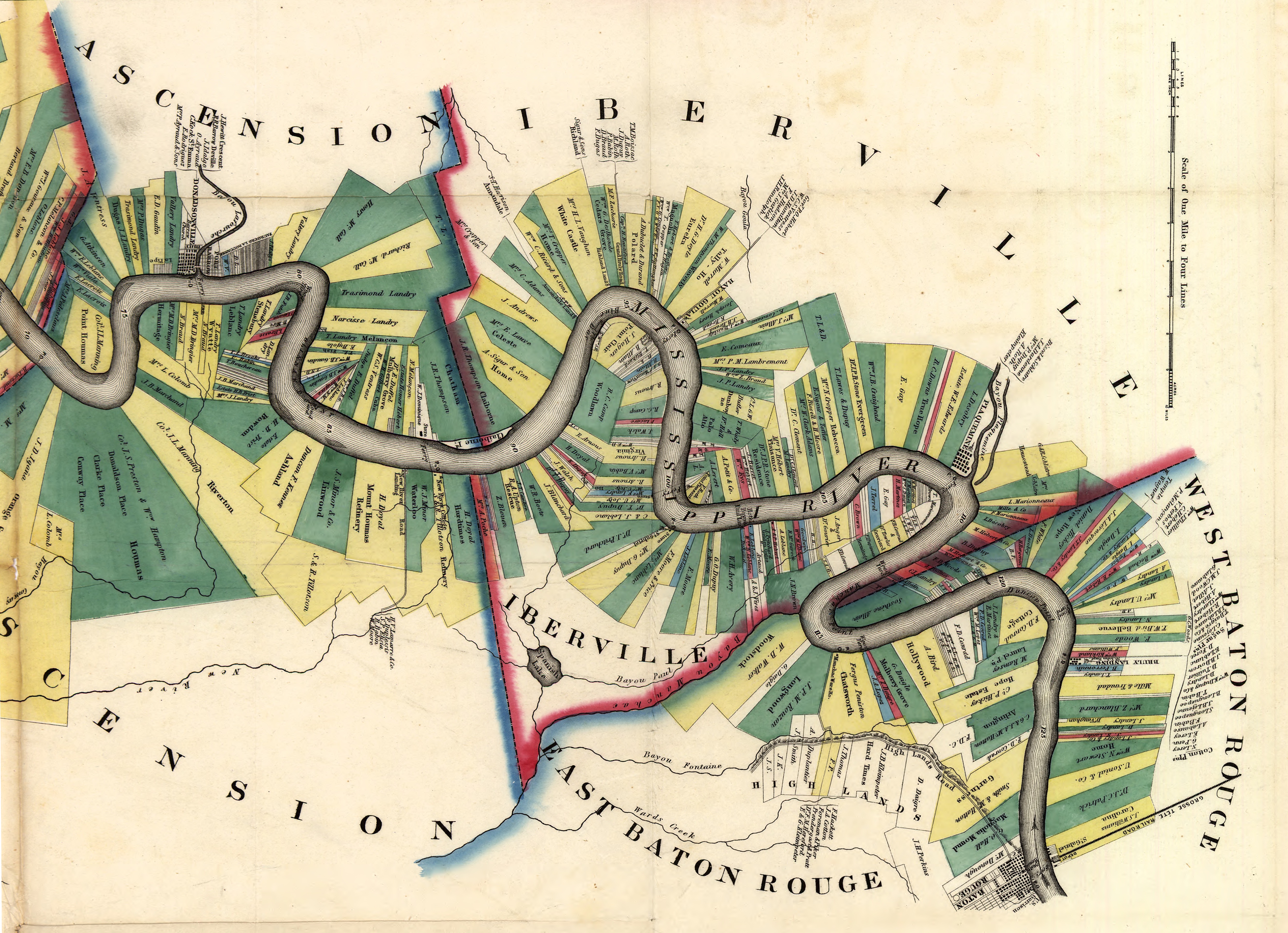

An example of one of these slave-owning families is the Cropper Family. Antoine Norbert Cropper was born in Iberville Parish, Louisiana. His father, Thomas Cropper, settled along the Mississippi River in Iberville Parish just shy on the year 1800. Thomas would go on to marry Julie Eulalie in 1802. Together they had two sons. They lived primarily at Laurel Ridge Plantation near White Castle, Louisiana.

Antoine Norbert Cropper married Henriette Lauve when he was 29 years old, and they had 5 children. Cropper was a troubled man, however. In August of 1855, while the family was returning from a trip to their summer home at Louisiana’s most affluent vacation spot, Isle Dernière — or Last Island — Cropper took his own life. Newspaper reports say, at the time of his death, Cropper was accompanied by an enslaved person who “was kept constantly by his side on the boat.”

Ironically, almost exactly a year later, his widow and several of their children were on Last Island when one of the most devastating storms in Louisiana’s history struck the narrow island. The results were catastrophic, and the once luxurious and fashionable watering hole was obliterated. According to NOAA, among the 401 people on the island, 198 died. Henriette, however, was dubbed a hero because, not only did she save herself and her children, she ensured the safety of her enslaved people, as well.

Needless to say, the Cropper family’s lives were evidently closely interconnected with the lives of their enslaved people. They were in each other’s company in intimate times, such as mental health crises or natural disasters. However, the Croppers, although bound by shared mortality, “owned” their enslaved companions.

Archival Documents Identifying Enslaved Individuals

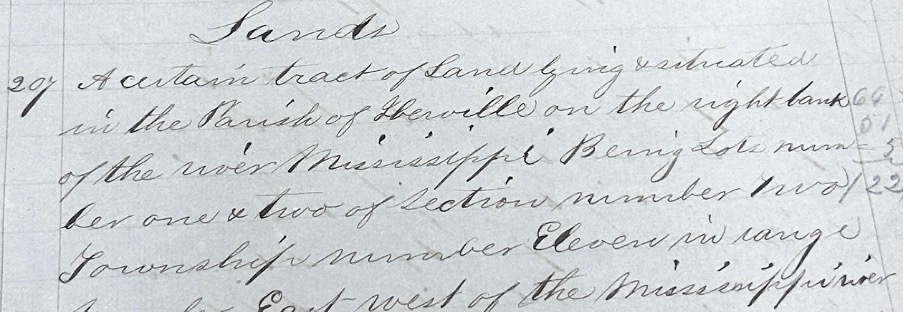

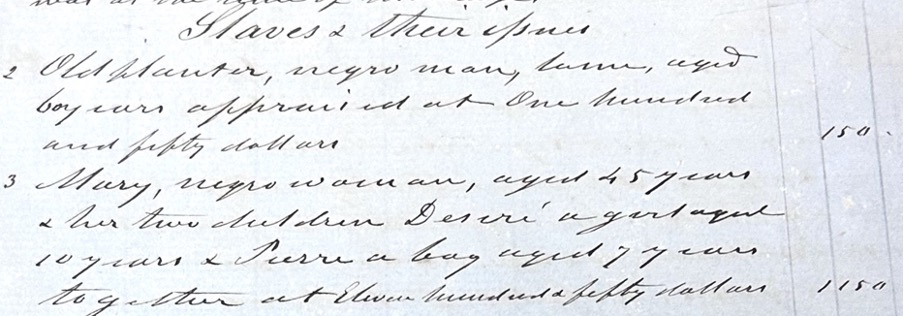

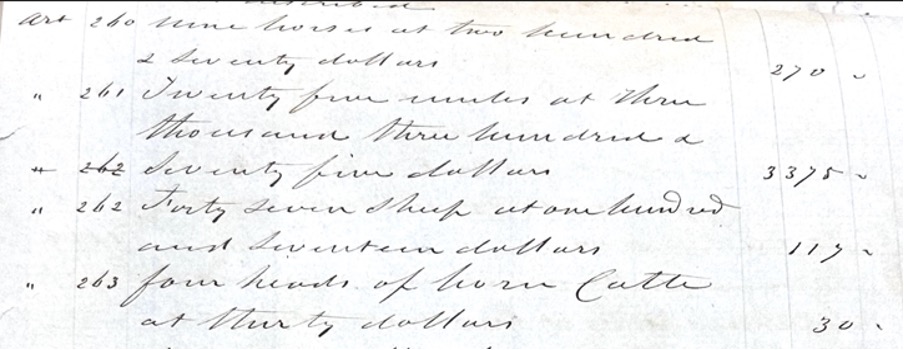

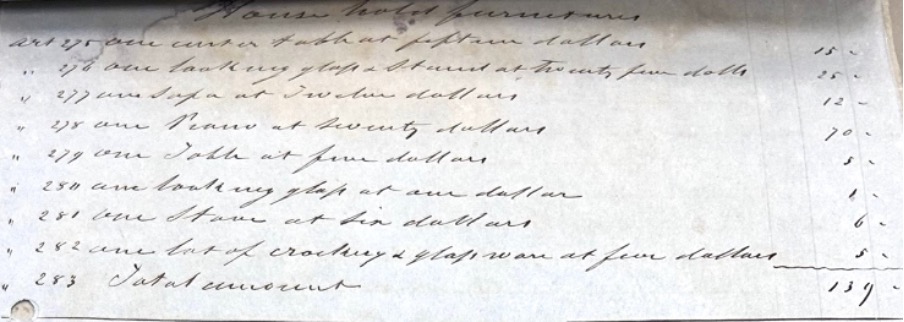

The Cropper’s were residents of Iberville Parish; therefore, their financial and legal documents can be found in the Iberville Parish Courthouse located in Plaquemine, Louisiana. Here, in a single document, it is possible to find land, people, livestock, and household items all listed similarly as types of property. In the succession inventory of the property of Antoine Norbert Cropper conducted after his death for example, the various categories of property listed are; “Lands,” “Slaves and their issues,” “Moveables” including 9 horses, 24 mules and 47 sheep, and “House hold Furnitures,” which consisted of items like a sofa, a piano, two looking glasses, and one lot of crockery and glassware.

Evidence of Multiple Generations of Enslaved People as Property

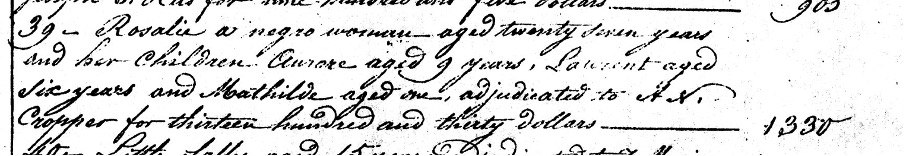

Amazingly, it is sometimes possible to trace the possession of enslaved people across multiple documents, and in some cases, to demonstrate matrilineal generations. As an example, an enslaved woman named Rosalie, along with her three children — Aurare, Laurent, and Mathilde — was purchased by Antoine Norbert Cropper from the estate of his mother-in-law, Marie Jeanne Guyot, in 1832 for $1,330. According to Rosalie’s description in the conveyance document, she was “a negro woman aged 27 years,” meaning she was born around 1804. The father of Rosalie’s children was not recorded.

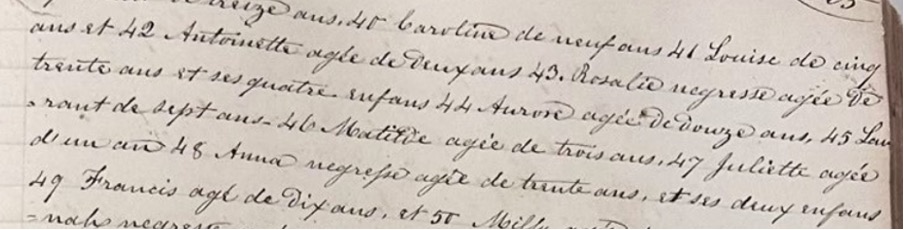

Rosalie appears next in 1834 in a marriage contract between the same Antoine Norbert Cropper and his prospective spouse, Henriette Lauve, in which the couple’s community property is detailed. In that record, Rosalie is described (in French) as 30 years old and accompanied by her now four children — Aurare, Laurant, Mathilde, and Juliette — aged between 12 and 1 years old. The father(s) of Rosalie’s children is again not recorded.

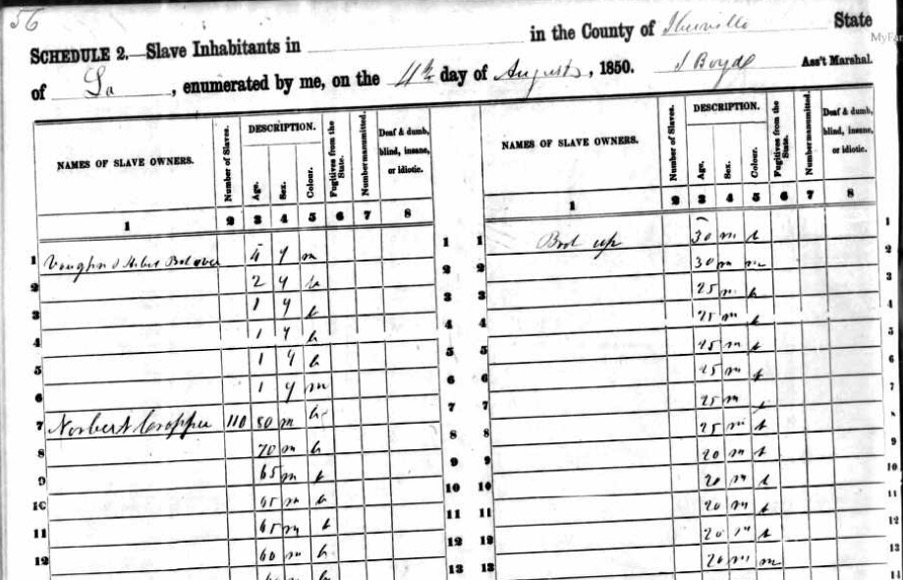

In an 1850 Slave Census, Antoine Norbert Cropper was reported as owning as many as 110 enslaved persons, but none are named.

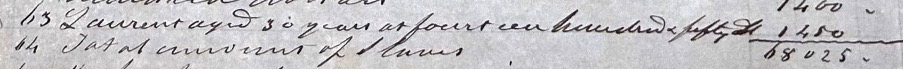

After Antoine Norbert Cropper’s death in 1855, an inventory of his property was conducted in February 1856. This document, which records the details of enslaved persons across at least three separate plantations, provides a wealth of information about Rosalie and her family.

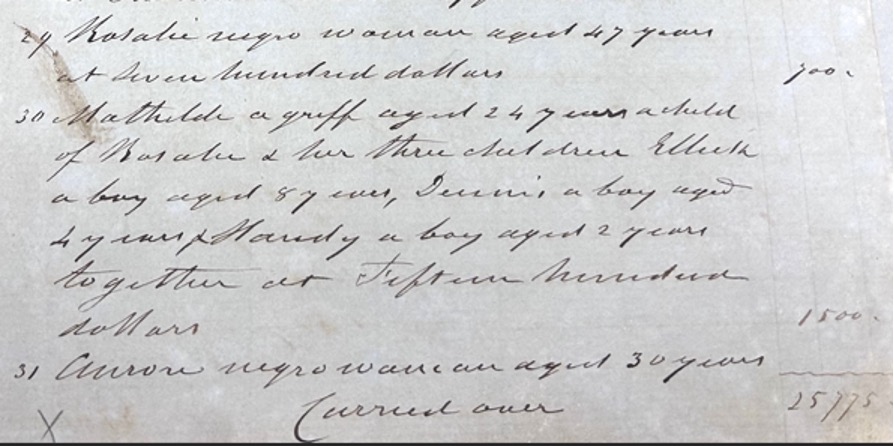

Rosalie herself is recorded in the inventory as “Rosalie, negro woman aged 47 years” valued at seven hundred dollars.

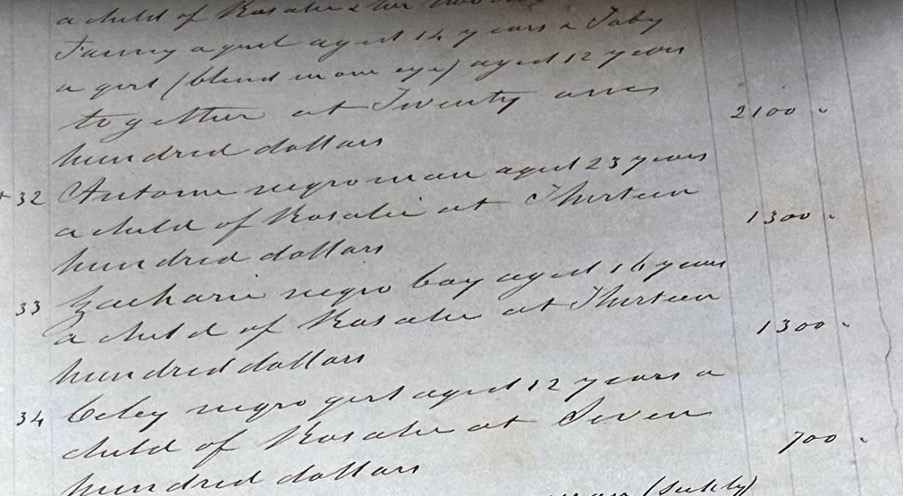

In the same document, Rosalie’s oldest child, Aurare, is listed with her own children (Rosalie’s grandchildren) as: “Aurare, negro woman aged 30 years, a child of Rosalie, and her two children Fanny, a girl aged 14 years, and Baby, a girl blind in one eye, aged 12 years—together at twenty-one hundred dollars.”

Rosalie’s son Laurant, from the prior records, is most likely the same as an enslaved man listed separately as 30 years old (born around 1825), valued at $1,450.

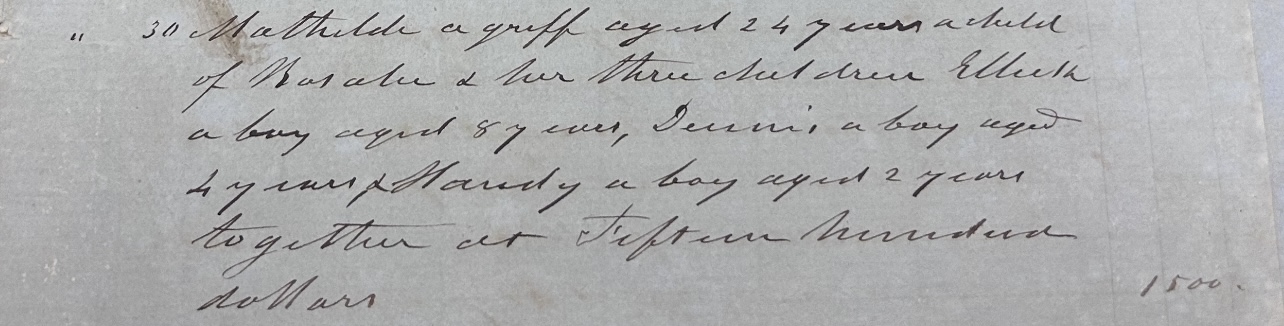

Rosalie’s daughter Mathilde, also from the prior records, is listed along with her children (Rosalie’s grandchildren) as: “a griffe aged 24 years a child of Rosalie and her three children Ellisha a boy aged 8 years, Dennis a boy aged 4 years, & Handy a boy aged 2 years together at fifteen hundred dollars.”

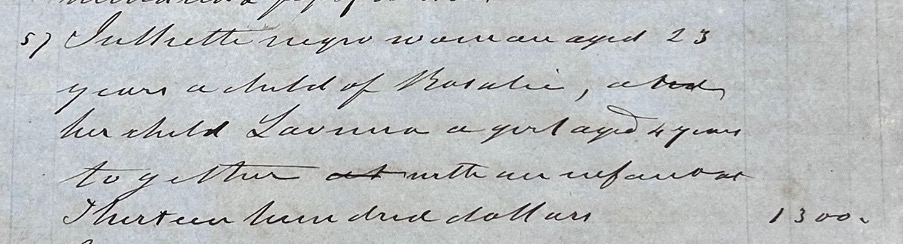

Rosalie’s daughter Juliette is listed with her daughter (Rosalie’s granddaughter) as: “Juliette, negro woman aged 23 years, a child of Rosalie, and her child Larissa, a girl aged 4 years, together with an infant at thirteen hundred dollars.”

Rosalie had at least four other children born after the date of the 1834 Contract of Marriage who are listed in the Inventory of Antoine Norbert Cropper. They were Antoine, born around 1834; Zacharia, born around 1840; Esther, born around 1841; and Celey, born around 1844. Each of these people are recorded as “a child of Rosalie,” although they are listed (and valued) separately.

The same opportunity to track an individual enslaved person across these documents exists for other individuals. For example, Francoise, born around 1816, can be traced through all three documents referenced above along with at least seven of her children. Others — including London, Joe Baker, Jesse, Peter, Wilson, Lucy/Little Lucy, Hannah, Nelly, Comfort, and Betsey — can also be tracked across at least two documents, often with children and sometimes grandchildren.

The Paradox of Enslaved People as Property

Archival records offer us the opportunity to explore the lives of enslaved people in greater depth. In cases like that of Rosalie, we are able to trace family members across several generations. Although not for certain, the documentation of familial ties — even between adult children and their own offspring — suggests that these relationships were acknowledged and perhaps held significance, even within financial ledgers.

Enslaved individuals were recorded alongside objects, like pianos and sofas, or livestock, yet they were human beings — no less complex, emotional, and real than the people who claimed to own them.

Sources:

Dixon, Bill. Last Days of Last Island: The Hurricane of 1856, Louisiana’s First Great Storm. Lafayette, LA: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2009.

Griffin-Elliott, Thia. “160th Anniversary of the Last Island Hurricane.” NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. August 10, 2016. https://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hurricane_blog/160th-anniversary-of-the-last-island-hurricane/.

Marriage Contract between Henriette Lauve and Antoine Norbert Cropper. Book O, entry 265, filed June 24, 1834. Conveyance Records. Iberville Parish Clerk of Court, Plaquemine, Louisiana.

“Melancholy Suicide.” Gazette and Sentinel, August 25, 1855.

“Norbert Cropper.” In Louisiana, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1756–1984. Ancestry.com. Accessed April 2025. https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/8055/records/90685891.

“Parish President, Sheriff Receive Opposition.” Plaquemine Post South, August 14, 2019. https://www.postsouth.com/story/news/2019/08/14/parish-president-sheriff-receive-opposition/4467406007/.

Riffel, Judy, ed. Iberville Parish History. Baton Rouge, LA: Le Comité des Archives de la Louisiane, 1985.

Succession of Antoine Norbert Cropper. No. 321. Filed January 15, 1856. Probate Records. Iberville Parish Clerk of Court, Plaquemine, Louisiana.

Succession of Marie Jeanne Guiot. No. 421. Filed October 10, 1831. Probate Records. Iberville Parish Clerk of Court, Plaquemine, Louisiana.