by Julia Schlorke

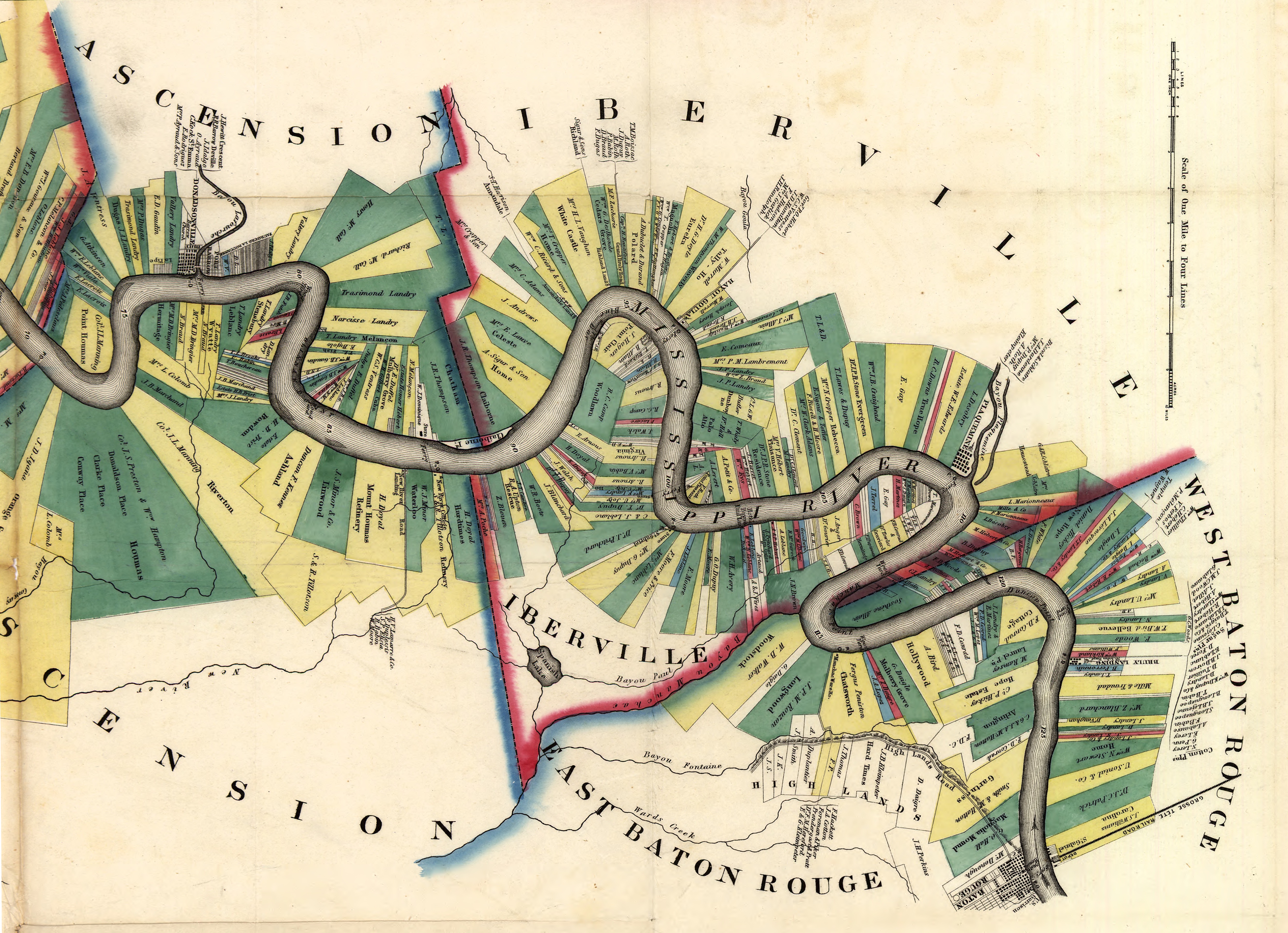

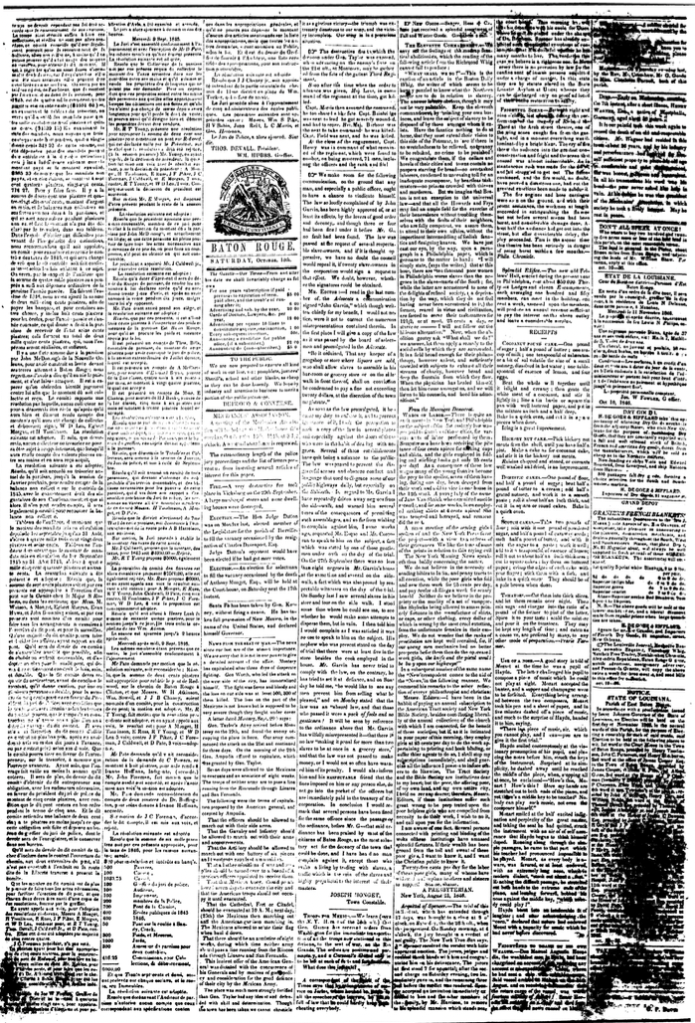

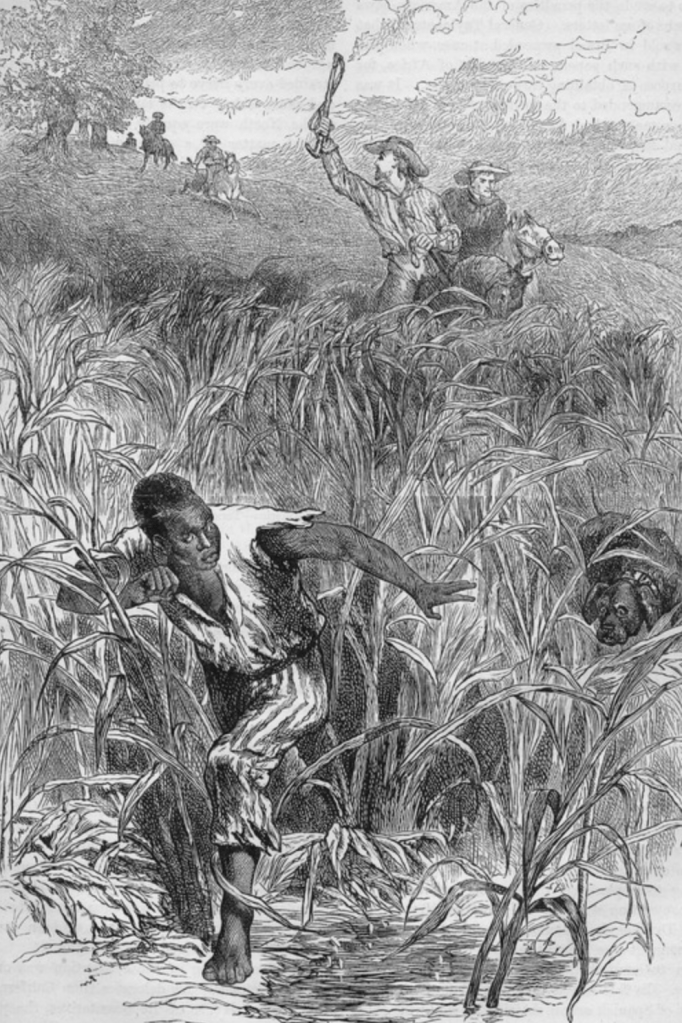

On a warm spring day in 1828, 30-year-old Odoway sat behind bars in a Baton Rouge jail. He had fled New Orleans and the man who claimed to own him. His name, age, and location were printed in the Baton Rouge Gazette alongside a simple yet telling note: the owner was requested to comply with the law and “take him away.” What the notice did not say, but could not erase, was that Odoway had chosen resistance. He had run nearly 80 miles in pursuit of freedom. Odoway’s story is not just a footnote in a legal document; it is a testament to the daily acts of courage undertaken by enslaved people across Baton Rouge. While white newspaper editors worked to maintain the institution of slavery, their pages inadvertently recorded a powerful counter-narrative. These newspapers revealed the resistance, autonomy, and quietly persistent pursuit of freedom. Despite their bias, newspapers became a lasting archive of the resistance of enslaved people.

Flight to Freedom

Odoway’s escape was far from an isolated attempt to find freedom. In that same Baton Rouge jail, two other men had also been captured in their escape attempt. Tom was from Ascension Parish, and Jesse was from Natchez. Like Odoway’s, their names were catalogued as property in need of retrieval, reminding slave owners of their legal obligation to pay the costs of their property’s imprisonment. These incarceration notices, routine for the time, reveal the broader truth that flight was one of the most common and persistent forms of Black resistance. It was not merely an escape; it was a rejection of ownership. The continual need to re-incarcerate escapees hints at the economic and emotional toll these acts of resistance played on slave owners. Each runaway was a financial liability and a reminder that control could never be complete.

Reclaiming Space

Other newspaper accounts reveal more subtle, yet powerful, methods of resistance. In 1846, Baton Rouge officials passed an ordinance to prevent enslaved people from gathering in grogshops or nearby sidewalks. While authorities justified the law as protecting public decency, it was clearly an attempt to sever relationships and limit community among enslaved people. The gatherings represented more than loitering; they were acts of reclaiming space. Mr. Garvin, a store owner who allowed such assemblies, was fined after multiple warnings. His defiance and the authorities’ frustration suggest that enslaved people continued to find ways to meet, talk, and bond in public. In doing so, they resisted the isolation that slavery sought to impose and built networks of support and survival.

Punishment to Power

When resistance could not be avoided or suppressed, slave owners turned to violent punishment. A July 1847 Weekly Advocate article reported that Peter, an enslaved man accused of burglary, was sentenced to 100 lashes and forced to wear an iron collar. His public punishment served as a warning to others, but simultaneously highlighted the presence of resistance and tension in the system. Whether or not Peter committed the crime, the state treated him as a legal subject. That inherently contradicts the idea that enslaved people were merely objects of property that were powerless and passive. Peter’s experience reminds us that resistance could be criminalized in order to preserve white dominance, and that enslaved people were willing to challenge that dominance even under the threat of brutality.

Resisting in the Margins

The myth of the “happy slave” or “benevolent slaveholder” has long persisted in American memory, but these newspaper records tell a very different story. Enslaved people were not waiting for white saviors or kind masters; they were active agents in their salvation. Their resistance took many forms: fleeing, taking up space, breaking rules, enduring punishment, and surviving with dignity. Even in a city like Baton Rouge, where laws and lashes tried to suppress them, Black people asserted their humanity. In the margins of history, they resisted. And in the yellowed pages of the Gazette and Advocate, we can still hear their voices.

Sources:

Baton-Rouge Gazette, 5 Apr. 1828

The Advocate, 14 July 1847.

“A Slave-Hunt.” Slavery Images, 1840s